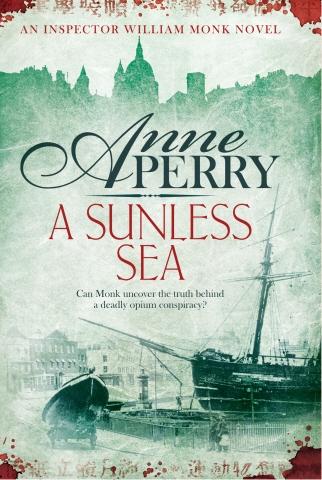

![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

you should …,” Monk began. Then he saw the level resolve in her eyes, and his words faded away. She would do it, whatever he said, for her own well-being, just as she had gone to the Crimea without her parents’ approval, and into the streets to create the clinic without his. It would have been very much more comfortable if she were to care more for her own well-being, or for his, certainly for her safety. But then the unhappiness would come in other ways, steadily mounting as she denied who she was and what she believed.

“At least be very careful!” he ended. “Think of Scuff!”

She hesitated, and colored a little. She drew in her breath as if to retaliate, then bit her lip. “I will,” she promised.

H ESTER BEGAN BY RETURNING to see Winfarthing. She was obliged to wait nearly an hour before he finished treating patients, then he gave her his entire attention. As usual, his office was littered with books and papers. A very small cat was curled up on the most thoroughly scattered heap, as if it had intentionally made them into a bed for itself. It did not stir when Hester sat down on the chair nearest to it.

Winfarthing did not appear to have noticed. He looked tired and unhappy. His thick hair was standing up on end where he had run his fingers through it.

“I don’t have anything that will help,” he said before she had time to ask. “I’d have told you if I had.”

She recounted to him what they had learned about Dinah and about Zenia Gadney.

“Good God!” he said with amazement, his face crumpled in an expression of profound pity. “I would do anything for her that I could, but what is there? If she didn’t kill the woman, then who did?” His expressionfilled with disgust. “I have no great love for politicians, or respect, either, but I find it very difficult to believe any one of them would cold-bloodedly murder Lambourn just to delay the Pharmacy Act. It will come sooner or later—probably sooner, whatever they do. Is there really so much money to be made in a year or two that it’s worth a man’s life? Not to mention a man’s soul?”

“No, I don’t think so,” she answered. “There has to be more to it, far more.”

He looked at her curiously. “What? Something that Lambourn knew and would have put in his report?”

“Don’t you think so?” She was uncertain now, fumbling for answers. She did not want Dinah to be guilty, or Joel Lambourn to be an incompetent suicide. Was that what was driving her, rather than reason? She saw the thought far too clearly in Winfarthing’s face, and felt the slight heat burn up her own cheeks.

“Lambourn’s suicide doesn’t make sense,” she said defensively. “The physical evidence is wrong.”

He ignored the argument. Perhaps it was irrelevant now anyway. “What are you thinking of?” he asked instead. “Something he discovered about the sale of opium? Smuggling? No one in Britain cares about the East India Company smuggling off the coast of China.” He snapped his fingers in the air in a gesture of dismissal. “China could be on Mars, for all it means to most of us—except their tea, silk, and porcelain, of course. But what happens there is nothing to the man in the street. Theft? In any moral sense it’s all theft: corruption, violence, and the poisoning of half a nation simply because we have the means and the desire to do it, and it’s absurdly profitable.”

“I don’t know!” Hester said again, a little more desperately. “There has to be something we do care about. We can butcher foreigners and find a way to justify it to ourselves but we can’t steal from our own, and we certainly can’t betray them.”

“And have we, Hester?” he said quietly. “What makes you think Lambourn discovered something like that? We all know that we introduced opium into China to pay for the luxuries we buy from them; we smuggle it into their country and it is killing them, an inch at a time.They go through caverns of the soul, measureless to man, down to a sunless sea. Read Coleridge—or De Quincey!”

“ ‘A sunless sea,’ ” she repeated. “That sounds like imprisonment, like drowning. How bad is real dependency on opium?”

He looked at her with sudden concentration, his eyes narrowed. “Why do you ask? Why now?”

“We don’t smoke it like the Chinese, we eat it, take it in medicines mixed with lots of other things,” she answered slowly. “It’s the only cure we have for the worst pain.”

“I

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher