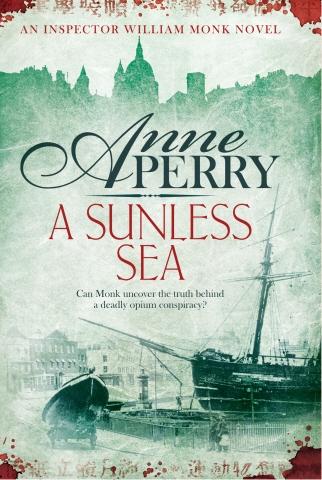

![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

life.”

“The opium report,” Bawtry said with a slight nod of understanding. “I didn’t know Lambourn personally. But I believe he was an unusually likable man, and affection can distort judgment, no matter how much you intend to be fair.”

“Exactly,” Monk agreed. He found himself relaxing a little. It was so much easier to deal with intellect unclouded by emotion.

Bawtry gave a tiny shrug, in a sort of wordless apology.

“A brilliant man, if a little unworldly,” he continued frankly. “Something of a crusader, and in this case, he allowed his intense pity for the victims of ignorance and desperation to color his overall view of the problem.” He lowered his voice a little. “To be honest, we do need some better control of what is put into medicines that anyone can buy, and certainly more information as to how much opium is in the medicines given to infants.”

He looked bleak. “But that is one of the main reasons we couldn’t accept Lambourn’s report. Some of his examples were extreme, and based more on anecdote than medical histories. It would have done more harm to the cause than good, because it could so easily have been discredited.”

He met Monk’s eyes with a steady gaze. “I’m sure you have the same problem preparing a criminal case for the courts. You must offer only the evidence that will stand up to cross-examination, the physical evidence you can produce, the witnesses whom people will believe. Anyone that the defense can destroy may lose you the jury.” He smiled, the question in his gesture. “He was a liability to us. I wish it had been different. He was a decent man.”

Then all the light vanished from his face. “I was stunned by his suicide. I had no idea he was so close to despair, but I have to believe there was something else far different from the failure of the report behind that. Perhaps something to do with this miserable business in Limehouse with the woman? I hope that isn’t the case—it would be so sordid. But I don’t know. My assessment of him is professional, not personal.”

“Do you know what happened to the report?” Monk asked. “I would like to see a copy of it.”

Bawtry looked surprised. “Do you think it can possibly have some bearing on the death of this woman? I find it hard to believe her connection with Lambourn is anything but coincidental.”

“Probably not,” Monk agreed. “But it would be remiss of me not to follow every lead. Perhaps she knew something? He may have spoken with her, even confided something to her concerning it.”

Bawtry frowned. “Like what? Do you mean the name of someone concerned with opium and patent medicines?”

“It’s possible.”

“I’ll find out if there is a copy still extant. If there is, I’ll see that you are given access to it.”

“Thank you.” There was nothing more that Monk could ask, and he had exhausted nearly all the time Bawtry could give him. He was not sure if it was what he had wanted to hear or hoped to discover, but he could not argue with it. It was careful, compassionate, and infinitely reasonable.

“Thank you, sir,” he said quietly.

Bawtry’s smile returned. “I hope it is of some use to you.”

CHAPTER

6

I N THE MORNING M ONK went to the office of the coroner who had dealt with Lambourn’s suicide. The findings of the inquest were public record and he had no difficulty in obtaining the papers.

“Very sad,” the clerk said to him solemnly. He was a young man who took his position gravely. His already receding hair was slicked back over his head and his dark suit was immaculate. “Anyone choosing to end their own life has to make one stop and think.”

Monk nodded, unable to find any reply worth making. He turned to the medical section of the report. Apparently Lambourn had taken a fairly large dose of opium, then slit his wrists and bled to death. The police surgeon had testified to it succinctly and no one had questioned either his accuracy or his skill. Indeed, there was no reason to.

The coroner had had no hesitation in passing a verdict of suicide, adding the usual compassion of presuming that the balance of the dead man’s mind had been affected, and therefore he was to be pitied rather than condemned. It was a pious form of words so customary as to be almost without meaning.

The commiserations were polite but formal. Lambourn had been a man much respected by his colleagues and no one wished to speculate aloud as to what might have been

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher