![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

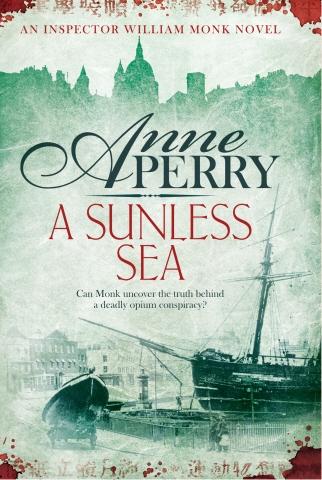

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

had responded,wishing he had not been foolish enough to allow himself to be drawn into this discussion.

Perhaps the man had been right. As he sat in the big, comfortable chair and looked at the papers spread out on his desk, he wondered if he had been rash. Had he accepted this as a sort of suicide of his own, a self-inflicted punishment for failing Margaret?

The newspapers were running banner headlines about the trial. Some journalists had described Dinah as a woman consumed with hatred toward her own sex. They suggested she was insanely jealous, given to delusions, and had driven Lambourn to suicide with her possessiveness.

Another paper’s editorial pointed out that if the jury sanctioned a woman committing a hideous and depraved murder because her husband had resorted to a prostitute, there was no end to the slaughter that that might lead to.

And of course Rathbone had heard some women siding with Dinah, saying that men who consorted with prostitutes defiled the marriage bed, not only by the betrayal of their vows, but more immediately and physically by the possibility of returning to a loyal wife and bringing to her the diseases of the whorehouse, and thus of course to their children. And what about the money such men lavished on their own appetites, even while in the act of denying their wives household necessities?

To some men whom Rathbone had overheard at his club, Dinah was the ultimate victim. To others she was the symbol of a hysterical woman seeking to limit all a man’s freedoms and to pursue his every move.

One writer had presented her as the heroine for all betrayed wives, for all women used, mocked, and then cast aside. The heat of emotion carried away reason like jetsam on a flood tide.

Rathbone had prepared everything he could for this defense, but he knew he had far too little. Neither Monk nor Orme had been able to find a witness who had seen Zenia with a man near the time of her death. The one person she had been seen with, briefly on the road by the river, was unquestionably a woman. He had no wish to draw attention to that.

All he really had to defend Dinah with was her past loyalties to both Lambourn and Zenia, and her character. He would rather not put her on the witness stand to testify. She was too vulnerable to ridicule because of her belief in a conspiracy for which there was no proof. But in the end he might have to.

Monk and Hester were still searching for solid evidence, as was Runcorn, when he had the chance. The trouble was, everything they had found so far could just as easily be interpreted as evidence of her guilt as her innocence.

The attack on Monk had been brutal, and well organized, but there was nothing to tie it to the murder of Zenia Gadney. There had been no second attack, so far.

Rathbone was glad when the clerk came to interrupt his growing sense of panic and call him to the courtroom. The trial was about to begin.

All the usual preliminaries were gone through. It was a ritual to which Rathbone hardly needed to pay attention. He looked up at the dock, where Dinah sat between two wardens, high above the floor of the court. On the left-hand wall, under the window, were jury benches, and ahead was the great chair in which the judge sat, resplendent in his scarlet robes and full-bottomed wig.

Rathbone studied them one by one while the voices droned on. Dinah Lambourn looked beautiful in her fear. Her eyes were wide, her skin desperately pale. Her thick, dark hair was pulled back a little severely to reveal the bones of her cheeks and brow, the perfect balance of her features, her generous, vulnerable mouth. He wondered if that would tell against her, or for her. Would the jury admire her dignity, or misunderstand it for arrogance? There was no way of knowing.

The judge was Grover Pendock, a man Rathbone had known for years, but never well. His wife was an invalid and he preferred to remain away from the social events to which she could not come. Was that in deference to her, or an admirable excuse to avoid a duty in which he had no pleasure? He had two sons. The elder, Hadley Pendock, was a sportsman of some distinction, and the judge was extremely proud of him. The younger one was more studious, it was said, and had yet to make his mark.

Rathbone looked up at Grover Pendock now and saw the general gravity of his rather large face, with its powerful jaw and thin mouth. This was a very public trial. He must know all eyes would be on his conduct of it,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher