![Write me a Letter]()

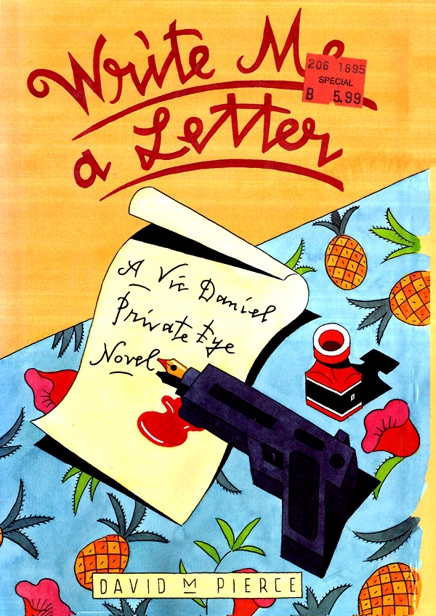

Write me a Letter

good morning to me. I said good morning to her. An elderly gent in jogging togs, breathing heavily, trotted by me. He said good morning. I said good morning. I passed an orange cat sitting under a tree. I said good morning.

I found Mr. Elkins’ home without any difficulty; it looked just like all the others. A well-maintained but elderly Chevy sat in the drive beside it. I knocked on Mr. Elkins’ aluminum-sided door. When it opened, I said to the man who opened it, ”Good morning.”

He said, ”Good morning.”

”Mr. Paul Horbovetz?” I said. ”That’s H-o-r-b-o-v-e-t-z.”

”Never heard of him,” he said, eyeing me carefully. As Katy had mentioned, he was an inoffensive-appearing little fellow, although I’m not sure I would have used the word sweet. He was maybe five foot seven or eight, bald as a coot, with a pleasant but unremarkable face, in his sixties probably, attired in a white shirt buttoned at both neck and cuffs and a pair of baggy black trousers that seemed to be belted somewhere just below his armpits. The belt was snakeskin, I perceived.

As for me, I merely smiled enigmatically. After a minute he sighed, then said, ”Oh, shit, you better come in out of the rain, whoever you are.”

I followed him in, over another nubbed carpet, into his rather sparsely furnished front room.

”I’ll tell you who I am,” I said. I told him. I even presented him with one of my business cards. He gave it a glance, then handed it back.

”That’s nice,” I said. ”In fact, that’s gorgeous.” I was referring to a wall hanging that was maybe three feet by six, it was a sort of Noah’s ark scene full of animals and birds and butterflies and jungle and clouds and sky and a crocodile or two. There was even an ark in it, with three windows—two were blank but the head of a man who looked remarkably like Mr. Paul Horbovetz appeared in the third. I walked over to get a closer look at it.

”Needlepoint, it’s called,” he said. ”I learned to do it up in Attica . I shared a cell for six months with what they call a child molester, Harry, he got me into it. Shit, it passes the time.”

”How much time would it take to do something like that?”

”On and off, a year,” he said. “You might as well sit down, I can see you’re planning on staying awhile.” I sat down carefully on the sofa. He sat in a straight chair by the bookcase.

”Well, here we are,” I said brightly.

”Ain’t we just,” he said. ”So what put you onto me?”

”Oh, a spot of elimination,” I said modestly. ”A spot of deductive reasoning. Mostly luck. Then I ran you through the computer, and bull’s-eye.”

”That I knew, didn’t I,” he said. ”As soon as you came up with my right name, you had to know my form, being a dick and all. Talk about a ghost from the past, shit, I’d almost forgotten what my real name was. Nine years I been here, can you believe it? Nine years of playing canasta and doffing my hat to old ladies with hearing aids. Stir crazy ain’t in it.”

”I can see how a man of the world like yourself might get a trifle bored here after a decade or so,” I said.

”Shit, I was bored after a week,” he said. ”But what’s a guy to do? I’d rather be alive and bored than dead and bored, any day.”

”So what happened?” I said. ”I hope you didn’t suddenly take off with a suitcase of greenbacks that didn’t belong to you. Someone else I know just did that very thing, giving me all kinds of problems, including French.”

”Nah,” he said. ”But I might as well of, I just took off, but when you’re in my line of work working for the types I was working for, you can forget about retiring and going to live on a chicken farm somewhere on your old-age pension. Something came up, a job, I didn’t like anything about it, so it was either disappear or get disappeared, if you get my meaning, friend.”

I allowed that I got the general tenor.

”Funny,” I said. ”That guy I just mentioned, I helped him to disappear, too, but I sure never thought of disappearing into the Senate Mobile Estate.”

”I never spent none of the money or nothing,” he said. ”Shit. I dunno. Maybe I can give it back.”

”So how come?” I said. ”If you didn’t need the money?”

”How come?” he said, getting up and walking around the room. ”How come is I can’t go to the track. How come is I can’t go to Reno , or Tahoe or Atlantic City . How come is I’m afraid to go bowling or to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher