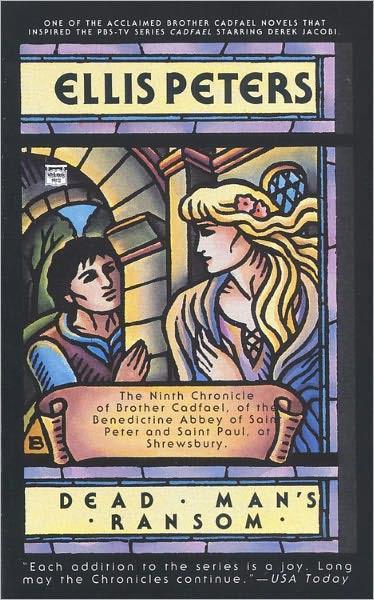

![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

and justice they had enjoyed under him, where much of England suffered a far worse fate.

So in his passing Gilbert had his due, and his people's weighty and deserved intercession for him with his God.

'No,' said Hugh, waiting for Cadfael as the brothers came out from Vespers that evening, 'nothing as yet. Crippled or not, it seems young Anion has got clean away. I've set a watch along the border, in case he's lying in covert this side till the hunt is called off, but I doubt he's already over the dyke. And whether to be glad or sorry for it, that's more than I know. I have Welsh in my own manor, Cadfael, I know what drives them, and the law that vindicates them where ours condemns. I've been a frontiersman all my life, tugged two ways.'

'You must pursue it,' said Cadfael with sympathy. 'You have no choice.'

'No, none. Gilbert was my chief,' said Hugh, 'and had my loyalty. Very little we two had in common, I don't know that I even liked him overmuch. But respect, yes, that we had. His wife is taking her son back to the castle tonight, with what little she brought here. I'm waiting now to conduct her.' Her stepdaughter was already departed with Sister Magdalen and the cloth, merchant's daughter, to the solitude of Godric's Ford. 'He'll miss his sister,' said Hugh, diverted into sympathy for the little boy.

'So will another,' said Cadfael, 'when he hears of her going. And the news of Anion's flight could not change her mind?'

'No, she's marble, she's damned him. Scold if you will,' said Hugh, wryly smiling, 'but I've let fall the word in his ear already that she's off to study the nun's life. Let him stew for a while, he owes us that, at least. And I've accepted his parole, his and the other lad's, Eliud. Either one of them has gone bail for himself and his cousin, not to stir a foot beyond the barbican, not to attempt escape, if I let them have the run of the wards. They've pledged their necks, each for the other. Not that I want to wring either neck, they suit very well as they are, untwisted, but no harm in accepting their pledges.'

'And I make no doubt,' said Cadfael, eyeing him closely, 'that you have a very sharp watch posted on your gates, and a very alert watchman on your walls, to see whether either of the two, or which of the two, breaks and runs for it.'

'I should be ashamed of my stewardship,' said Hugh candidly, 'if I had not.'

'And do they know, by this time, that a bastard Welsh cowman in the abbey's service has cast his crutch and run for his life?'

'They know it. And what do they say? They say with one voice, Cadfael, that such a humble soul and Welsh into the bargain, without kin or privilege here in England, would run as soon as eyes were cast on him, sure of being blamed unless he could show he was a mile from the matter at the fatal time. And can you find fault with that? It's what I said myself when you brought me the same news.'

'No fault,' said Cadfael thoughtfully. 'Yet matter for consideration, would you not say? From the threatened to the threatened, that's large grace.'

Chapter Nine.

Owain Gwynedd sent back his response to the events at Shrewsbury on the day after Anion's flight, by the mouth of young John Marchmain, who had remained in Wales to stand surety for Gilbert Prestcote in the exchange of prisoners. The half dozen Welsh who had escorted him home came only as far as the gates of the town, and there saluted and withdrew again to their own country.

John, son to Hugh's mother's younger sister, a gangling youth of nineteen, rode into the castle stiff with the dignity of the embassage with which he was entrusted, and reported himself ceremoniously to Hugh.

'Owain Gwynedd bids me say that in the matter of a death so brought about, his own honour is at stake, and he orders his men here to bear themselves in patience and give all possible aid until the truth is known, the murderer uncovered, and they vindicated and free to return. He sends me back as freed by fate. He says he has no other prisoner to exchange for Elis ap Cynan, nor will he lift a finger to deliver him until both guilty and innocent are known.'

Hugh, who had known him from infancy, hoisted impressed eyebrows into his dark hair, whistled and laughed. 'You may stoop now, you're flying too high for me.'

'I speak for a high flying hawk,' said John, blowing out a great breath and relaxing into a grin as he leaned back against the guard, room wall. 'Well you've understood him. That's the elevated tenor of it. He

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher