![Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice]()

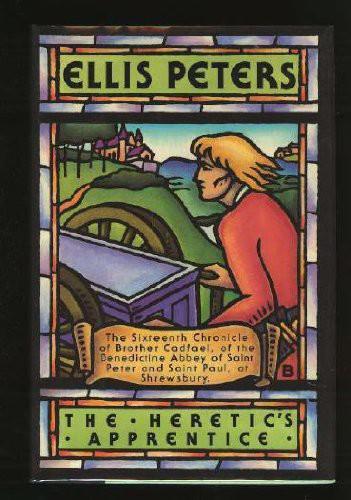

Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice

way."

"He's nephew to Father Eadmer at Attingham, and named for his uncle. Whether he's there still, with him, is more than I know. But he has no cure yet. I would go," said Boniface, hesitating, "but I could hardly get back for Vespers. If I'd thought of it earlier..."

"Never trouble yourself," said Cadfael. "I'll ask leave of Father Abbot and go myself. For such a cause he'll give permission. It's the welfare of a soul at stake. And in this warm weather," he added practically, "there's need of haste."

It was, as it chanced, the first day for over a week to grow lightly overcast, though before night the cloud cover cleared again. To set out along the Foregate with the abbot's blessing behind him and a four-mile walk ahead was pure pleasure, and the lingering vagus left in Cadfael breathed a little deeper when he reached the fork of the road at Saint Giles, and took the left-hand branch towards Attingham. There were times when the old wandering desire quickened again within him, and the very fact that he had been sent on an errand even beyond the limits of the shire, only three months back, in March, had rather roused than quenched the appetite. The vow of stability, however gravely undertaken, sometimes proved as hard to keep as the vow of obedience, which Cadfael had always found his chief stumbling block. He greeted this afternoon's freedom - and justified freedom, at that, since it had sanction and purpose - as a refreshment and a holiday.

The highroad had a broad margin of turf on either side, soft green walking, the veil of cloud had tempered the sun's heat, the meadows were green on either hand, full of flowers and vibrant with insects, and in the bushes and headlands of the fields the birds were loud and full of themselves, shrilling off rivals, their first brood already fledged and trying their wings. Cadfael rolled contentedly along the green verge, the grass stroking silken cool about his ankles. Now if the end came up to the journey, every step of the way would be repaid with double pleasure.

Before him, beyond the level of fields, rose the wooded hogback of the Wrekin, and soon the river reappeared at some distance on his left, to wind nearer as he proceeded, until it was close beside the highway, a gentle, innocent stream between flat grassy banks, incapable of menace to all appearances, though the local people knew better than to trust it. There were cattle in the pastures here, and waterfowl among the fringes of reeds. And soon he could see the square, squat tower of the parish church of Saint Eata beyond the curve of the Severn, and the low roofs of the village clustered close to it. There was a wooden bridge somewhat to the left, but Cadfael made straight for the church and the priest's house beside it. Here the river spread out into a maze of green and golden shallows, and at this summer level could easily be forded. Cadfael tucked up his habit and splashed through, shaking the little rafts of water crowfoot until the whole languid surface quivered.

Over the years, summer by summer, so many people had waded the river here instead of turning aside to the bridge that they had worn a narrow, sandy path up the opposite bank and across the grassy level between river and church, straight to the priest's house. Behind the mellow red stone of the church and the weathered timber of the modest dwelling in its shadow a circle of old trees gave shelter from the wind, and shaded half of the small garden. Father Eadmer had been many years in office here, and worked lovingly upon his garden. Half of it was producing vegetables for his table, and by the look of it a surplus to eke out the diet of his poorer neighbours. The other half was given over to a pretty little herber full of flowers, and the undulation of the ground had made it possible for him to shape a short bench of earth, turfed over with wild thyme, for a seat. And there sat Father Eadmer in his midsummer glory, a man lavish but solid of flesh, his breviary unopened on his knees, his considerable weight distilling around him, at every movement, a great aureole of fragrance. Before him, hatless in the sun, a younger man was busy hoeing between rows of young cabbages, and the gleam of his shaven scalp above the ebullient ring of curly hair reassured Cadfael, as he approached, that he had not had his journey for nothing. At least enquiry was possible, even if it produced disappointing answers.

"Well, well!" said the elder Eadmer, sitting up

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher