![Gone Missing (Kate Burkholder 4)]()

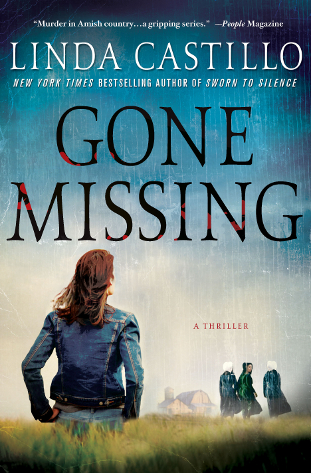

Gone Missing (Kate Burkholder 4)

mention their daughter’s suicide; I don’t believe its relevant. Nor do I believe they’re involved in the disappearances. Nonetheless they’ve got some explaining to do.

I’ve spent the last two hours racking my brain, trying to hit on some common denominator that connects the missing teens: Annie King, Bonnie Fisher, Ruth Wagler, Sadie Miller, and, finally, Noah Mast.

Aside from being Amish, what did these five young people have in common? We haven’t been able to determine if they knew one another or if they’d been in contact with one another. In all probability, mainly due to the physical distance between them and limited transportation options, they did not. As far as we know, none of the teenagers had access to a computer or laptop, so they probably didn’t meet online. Of course, they could have used a public computer—at a library, for example—but I don’t think that’s the case.

The most obvious characteristic they shared was that they were Amish. Second, all were between fourteen and eighteen years of age. I think about what events take place during that period of time in the life of an Amish teenager. Since most only go to school through the eighth grade, they would have finished by age fourteen and already have been considering joining the church. Some were already working, either on the farm or, depending on where they lived, outside the home. Some had entered rumspringa, which is basically a period of one or two years when the teenager is granted the freedom to experience the outside world before being baptized.

My gut tells me that while age is key, the element that connects these teens is more personal. Something unique to these particular teenagers. But what? What are we not seeing? Why the hell doesn’t anything about this case feel right?

I know, perhaps better than most, that the Amish keep secrets. Even conservative Amish families do. My own family, while not exactly Old Order, were conservative. My mamm and datt held my sister and brother and me to some pretty high standards, even in terms of the Amish. Jacob and Sarah fared well beneath that kind of iron-fist parenting. Neither strayed beyond the parameters of the Ordnung.

But I floundered within those constraints. Even as young as twelve, I resented the restrictions imposed on my life, even though I had no inkling of the concept of freedom. I remember feeling as if every aspect of my life was being micromanaged—by my parents, by our bishop, by society and the Amish culture in general. I recall begrudging my brother because he—and Amish males in general—had more freedoms than I and my female peers did. Even then, the unfairness of that chafed my sensibilities.

All of that discontent came to a head when I was fourteen and an Amish man by the name of Daniel Lapp walked into our farmhouse when I was alone and raped me. I learned the meaning of violence that day. I learned to what lengths I would go to protect myself. And I learned that I was capable of extreme violence. I learned what it meant to hate—not only another human being but myself. Especially myself.

When my parents discovered I’d shot and killed my rapist, I learned that even decent, God-loving Amish break the law. I learned they’re capable of lying to protect their children. And, in the eyes of the angry teen I’d been, I knew that underneath all those layers of self-righteous bullshit, they were sinners, just like everyone else.

I spent the following years rebelling against any rule that didn’t suit me—and few did. I defied my parents. I railed against all those rigid Amish tenants. I rebelled against myself, and against God. I disrupted the lives of my siblings. Embarrassed my parents. Disappointed the Amish bishop. When Mamm and Datt began to worry that I was a negative influence on my siblings, I knew it was time to leave. The thought terrified me, but I would rather have died than admit it. Instead, when I turned eighteen, I left Painters Mill for Columbus, Ohio.

In the back of my mind, I always thought I’d fail. That I’d run back to Painters Mill with my tail between my legs. But I didn’t. Mamm traveled to Columbus when I graduated from the Police Academy. Sadly, I never saw my datt again. He died of a stroke six months later. I finally returned to Painters Mill to be with Mamm after she’d been diagnosed with breast cancer. She’d forgone conventional medical treatment, opting instead for Amish folk remedies. Those remedies did

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher