![Mercy Thompson 01-05 - THE MERCY THOMPSON COLLECTION]()

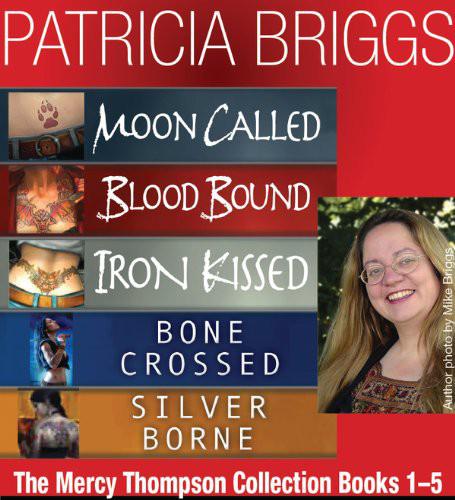

Mercy Thompson 01-05 - THE MERCY THOMPSON COLLECTION

I picked up from my human foster mother, Evelyn.

âI was stupid and young,â I said. âI needed to hear what you told me. So if youâre looking for forgiveness, you donât need it. Thank you.â

He cocked his head. In human form his eyes were warm hazel, like a sunlit oak leaf.

âIâm not apologizing,â he said. âNot to you. Iâm explaining.â Then he smiled, and the resemblance to Samuel, usually faint, was suddenly very apparent. âAnd Samuel is a wee bit older than sixty.â Amusement, like anger, sometimes brought a touch of the old countryâWalesâto Branâs voice. âSamuel is my firstborn.â

I stared at him, caught by surprise. Samuel had none of the traits of the older wolves. He drove a car, had a stereo system and a computer. He actually liked peopleâeven humansâand Bran used him to interface with police and government officials when it was necessary.

âCharles was born a few years after you came here with David Thompson,â I told Bran, as if he didnât know. âThat was what . . . 1812?â Driven by his association to Bran, Iâd done a lot of reading about David Thompson in college. The Welsh-born mapmaker and fur trader had kept journals, but he hadnât ever mentioned Bran by name. I wondered when I read them if Bran had gone by another name, or if Thompson had known what Bran was and left him out of the journals, which were kept, for the most part, more as a record for his employers than as a personal reminiscence.

âI came with Thompson in 1809,â Bran said. âCharles was born in the spring of, I think, 1813. Iâd left Thompson and the Northwest Company by then, and the Salish didnât reckon time by the Christian calendar. Samuel was born to my first wife, when I was still human.â

It was the most Iâd ever heard him say about the past. âWhen was that?â I asked, emboldened by his uncustomary openness.

âA long time ago.â He dismissed it with a shrug. âWhen I talked to you that night, I did my son a disservice. I have decided that perhaps I was overzealous with the truth and still only gave you part of it.â

âOh?â

âI told you what I knew, as much as I thought necessary at the time,â he said. âBut in light of subsequent events, I underestimated my son and led you to do the same.â

Iâve always hated it when he chose to become obscure. I started to object sharplyâthen realized he was looking away from my face, his eyes lowered. Iâd gotten used to living among humans, whose body language is less important to communication, so Iâd almost missed it. Alphasâespecially this Alphaânever looked away when others were watching them. It was a mark of how bad he felt that he would do it now.

So I kept my voice quiet, and said simply, âTell me now.â

âSamuel is old,â he said. âNearly as old as I am. His first wife died of cholera, his second of old age. His third wife died in childbirth. His wives miscarried eighteen children between them; a handful died in infancy, and only eight lived to their third birthday. One died of old age, four of the plague, three of failing the Change. He has no living children and only one, born before Samuel Changed, made it into adulthood.â

He paused and lifted his eyes to mine. âThis perhaps gives you an idea of how much it meant to him that in you heâd found a mate who could give him children less vulnerable to the whims of fate, children who could be born werewolves like Charles was. I have had a long time to think about our talk, and I came to understand that I should have told you this as well. You arenât the only one who has mistaken Samuel for a young wolf.â He gave me a little smile. âIn the days Samuel walked as human, it was not uncommon for a sixteen-year-old to marry a man much older than she. Sometimes the world shifts its ideas of right and wrong too fast for us to keep up with it.â

Would it have changed how I felt to know the extent of Samuelâs need? A passionate, love-starved teenager confronted with cold facts? Would I have seen beyond the numbers to the pain that each of those deaths had cost?

I donât think it would have changed my decision. I knewthat because I still wouldnât have married someone who didnât love me; but I think I would have

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher