![Pnin]()

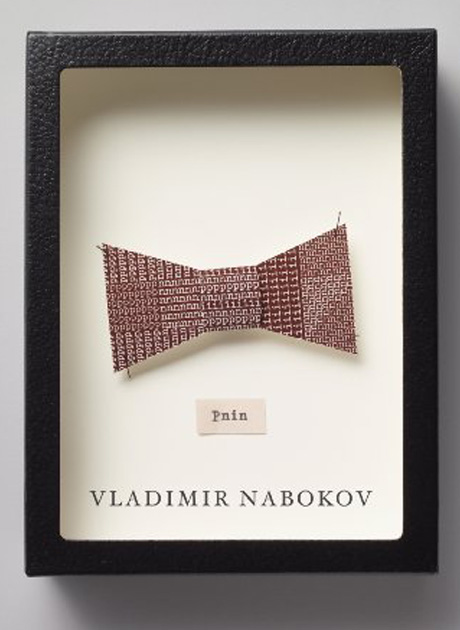

Pnin

think he loved anybody.

In his attitude toward his mother, passionate childhood affection had long since been replaced by tender condescension, and all he permitted himself was an inward sigh of amused submission to fate when, in her fluent and flashy New York English, with brash metallic nasalities and soft lapses into furry Russianisms, she regaled strangers in his presence with stories that he had heard countless times and that were either over-embroidered or untrue. It was more trying when among such strangers Dr Eric Wind, a completely humourless pedant who believed that his English (acquired in a German high school) was impeccably pure, would mouth a stale facetious phrase, saying 'the pond' for the ocean, with the confidential and arch air of one who makes his audience the precious gift of a fruity colloquialism. Both parents, in their capacity of psychotherapists, did their best to impersonate Laius and Jocasta, but the boy proved to be a very mediocre little Oedipus. In order not to complicate the modish triangle of Freudian romance (father, mother, child), Liza's first husband had never been mentioned. Only when the Wind marriage started to disintegrate, about the time that Victor was enrolled at St Bart's, Liza informed him that she had been Mrs Pnin before she left Europe. She told him that this former husband of hers had migrated to America too - that in fact he would soon see Victor; and since everything Liza alluded to (opening wide her radiant black-lashed blue eyes) invariably took on a veneer of mystery and glamour, the figure of the great Timofey Pnin, scholar and gentleman, teaching a practically dead language at the famous Waindell College some three hundred miles north-west of St Bart's, acquired in Victor's hospitable mind a curious charm, a family resemblance to those Bulgarian kings or Mediterranean princes who used to be world-famous experts in butterflies or sea shells. He therefore experienced pleasure when Professor Pnin entered into a staid and decorous correspondence with him; a first letter, couched in beautiful French but very indifferently typed, was followed by a picture postcard representing the Grey Squirrel. The card belonged to an educational series depicting Our Mammals and Birds; Pnin had acquired the whole series specially for he purpose of this correspondence. Victor was glad to earn that' squirrel' came from a Greek word which meant shadow-tail'. Pnin invited Victor to visit him during the next vacation and informed the boy that he would meet um at the Waindell bus station. 'To be recognized,' he wrote, in English, 'I will appear in dark spectacles and hold a black brief-case with my monogram in silver.'

3

Both Eric and Liza Wind were morbidly concerned with heredity, and instead of delighting in Victor's artistic genius, they used to worry gloomily about its genetic cause. Art and science had been represented rather vividly in the ancestral past. Should one trace Victor's passion for pigments back to Hans Andersen (no relation to the bedside Dane), who had been a stained-glass artist in Lübeck before losing his mind (and believing himself to be a cathedral) soon after his beloved daughter married a grey-haired Hamburg jeweller, author of a monograph on sapphires, and Eric's maternal grandfather? Or was Victor's almost pathological precision of pencil and pen a by-product of Bogolepov's science? For Victor's mother's great-grandfather, the seventh son of a country pope, had been no other than that singular genius, Feofilakt Bogolepov, whose only rival for the title of greatest Russian mathematician was Nikolay Lobachevski. One wonders.

Genius is non-conformity. At two, Victor did not make little spiral scribbles to express buttons or port-holes, as a million tots do, why not you? Lovingly he made his circles perfectly round and perfectly closed. A three-year-old child, when asked to copy a square, shapes one recognizable corner and then is content to render the rest of the outline as wavy or circular; but Victor at three not only copied the researcher's (Dr Liza Wind's) far from ideal square with contemptuous accuracy but added a smaller one beside the copy. He never went through that initial stage of graphic activity when infants draw Kopffüsslers (tadpole people), or humpty dumpties with L-like legs, and arms ending in rake prongs; in fact, he avoided the human form altogether and when pressed by Papa (Dr Eric Wind) to draw Mama (Dr Liza Wind), responded with a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher