![Pnin]()

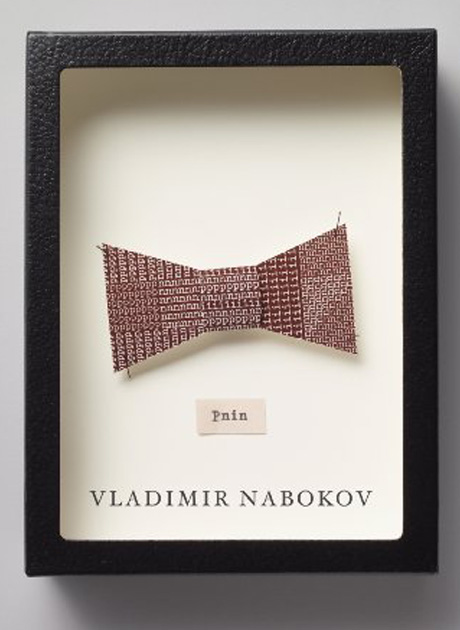

Pnin

Buddha-like, in a curiously neat studio that looked more like a reception room in an art gallery than a workshop. Nothing adorned its pale grey walls except two identically framed pictures: a copy of Gertrude K ä sebier's photographic masterpiece 'Mother and Child' (1897), with the wistful, angelic infant looking up and away (at what?); and a similarly toned reproduction of the head of Christ from Rembrandt's 'The Pilgrims of Emmaus', with the same, though slightly less celestial, expression of eyes and mouth.

He had been born in Ohio, had studied in Paris and Rome, had taught in Ecuador and Japan. He was a recognized art expert, and it puzzled people why, during the past ten winters, Lake chose to bury himself at St Bart's. While endowed with the morose temper of genius, he lacked originality and was aware of that lack; his own paintings always seemed beautifully clever imitations, although one could never quite tell whose manner he mimicked. His profound knowledge of innumerable techniques, his indifference to 'schools' and 'trends', his detestation of quacks, his conviction that there was no difference whatever between a genteel aquarelle of yesterday and, say, conventional neoplasticism or banal non-objectivism of today, and that nothing but individual talent mattered - these views made of him an unusual teacher. St Bart's was not particularly pleased either with Lake's methods or with their results, but kept him on because it was fashionable to have at least one distinguished freak on the staff. Among the many exhilarating things Lake taught was that the order of the solar spectrum is not a closed circle but a spiral of tints from cadmium red and oranges through a strontian yellow and a pale paradisal green to cobalt blues and violets, at which point the sequence does not grade into red again but passes into another spiral, which starts with a kind of lavender grey and goes on to Cinderella shades transcending human perception. He taught that there is no such thing as the Ashcan School or the Cache Cache School or the Cancan School. That the work of art created with string, stamps, a Leftist newspaper, and the droppings of doves is based on a series of dreary platitudes. That there is nothing more banal and more bourgeois than paranoia. That Dali is really Norman Rockwell's twin brother kidnapped by gipsies in babyhood. That Van Gogh is second-rate and Picasso supreme, despite his commercial foibles; and that if Degas could immortalize a ca lè che, why could not Victor Wind do the same to a motor car?

One way to do it might be by making the scenery penetrate the automobile. A polished black sedan was a good subject, especially if parked at the intersection of a tree-bordered street and one of those heavyish spring skies whose bloated grey clouds and amoeba-shaped blotches of blue seem more physical than the reticent elms and evasive pavement. Now break the body of the car into separate curves and panels; then put it together in terms of reflections. These will be different for each part: the top will display inverted trees with blurred branches growing like roots into a washily photographed sky, with a whalelike building swimming by - an architectural afterthought; one side of the hood will be coated with a band of rich celestial cobalt; a most delicate pattern of black twigs will be mirrored in the outside surface of the rear window; and a remarkable desert view, a distended horizon, with a remote house here and alone tree there, will stretch along the bumper. This mimetic and integrative process Lake called the necessary 'naturalization' of man-made things. In the streets of Cranton, Victor would find a suitable specimen of car and loiter around it. Suddenly the sun, half masked but dazzling, would join him. For the sort of theft Victor was contemplating there could be no better accomplice. In the chrome plating, in the glass of a sun-rimmed headlamp, he would see a view of the street and himself comparable to the microcosmic version of a room (with a dorsal view of diminutive people) in that very special and very magical small convex mirror that, half a millennium ago, Van Eyck and Petrus Christus and Memling used to paint into their detailed interiors, behind the sour merchant or the domestic Madonna.

To the latest issue of the school magazine Victor had contributed a poem about painters, over the nom de guerre Moinet, and under the motto 'Bad reds should all be avoided; even if carefully manufactured,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher