![Pnin]()

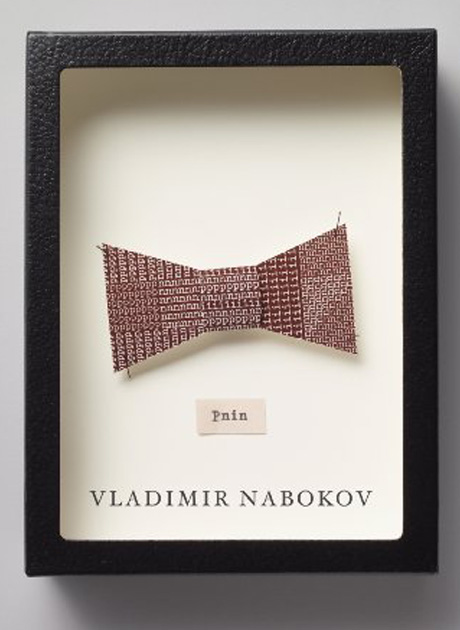

Pnin

they are still bad' (quoted from an old book on the technique of painting but smacking of a political aphorism). The poem began:

Leonardo! Strange diseases

strike at madders mixed with lead:

nun-pale now are Mona Lisa's

lips that you had made so red.

He dreamed of mellowing his pigments as the Old Masters had done - with honey, fig juice, poppy oil, and the slime of pink snails. He loved water colours and he loved oils, but was wary of the too fragile pastel and the too coarse distemper. He studied his mediums with the care and patience of an insatiable child - one of those painter's apprentices (it is now Lake who is dreaming!), lads with bobbed hair and bright eyes who would spend years grinding colours in the workshop of some great Italian skiagrapher, in a world of amber and paradisal glazes. At eight, he had once told his mother that he wanted to paint air. At nine, he had known the sensuous delight of a graded wash. What did it matter to him that gentle chiaroscuro, offspring of veiled values and translucent undertones, had long since died behind the prison bars of abstract art, in the poorhouse of hideous primitivism? He placed various objects in turn - an apple, a pencil, a chess pawn, a comb - behind a glass of water and peered through it at each studiously: the red apple became a clear-cut red band bounded by a straight horizon, half a glass of Red Sea, Arabia Felix. The short pencil, if held obliquely, curved like a stylized snake, but if held vertically became monstrously fat - almost pyramidal. The black pawn, if moved to and fro, divided into a couple of black ants. The comb, stood on end, resulted in the glass's seeming to fill with beautifully striped liquid, a zebra cocktail.

6

On the eve of the day on which Victor had planned to arrive, Pnin entered a sport shop in Waindell's Main Street and asked for a football. The request was unseasonable but he was offered one.

'No, no,' said Pnin, 'I do not wish an egg or, for example, a torpedo. I want a simple football ball. Round!'

And with wrists and palms he outlined a portable world. It was the same gesture he used in class when speaking of the 'harmonical wholeness' of Pushkin.

The salesman lifted a finger and silently fetched a soccer ball.

'Yes, this I will buy,' said Pnin with dignified satisfaction.

Carrying his purchase, wrapped in brown paper and Scotch-taped, he entered a bookstore and asked for Martin Eden.

'Eden, Eden, Eden,' the tall dark lady in charge repeated rapidly, rubbing her forehead. 'Let me see, you don't mean a book on the British statesman? Or do you?'

'I mean,' said Pnin, 'a celebrated work by the celebrated American writer Jack London.'

'London, London, London,' said the woman, holding her temples.

Pipe in hand, her husband, a Mr Tweed, who wrote topical poetry, came to the rescue. After some search he brought from the dusty depths of his not very prosperous store an old edition of The Son of the Wolf.

'I'm afraid,' he said, 'that's all we have by this author.'

'Strange!' said Pnin. 'The vicissitudes of celebrity! In Russia, I remember, everybody - little children, full-grown people, doctors, advocates - everybody read and re-read him. This is not his best book but O.K., O.K., I will take it.'

On coming home to the house where he roomed that year, Professor Pnin laid out the ball and the book on the desk of the guest room upstairs. Cocking his head, he surveyed these gifts. The ball did not look nice in its shapeless wrapping; he disrobed it. Now it showed its handsome leather. The room was tidy and cosy. A schoolboy should like that picture of a snowball knocking off a professor's top hat. The bed had just been made by the cleaning woman; old Bill Sheppard, the landlord, had come up from the first floor and had gravely screwed a new bulb into the desk lamp. A warm humid wind pressed through the open window, and one could hear the noise of an exuberant creek that ran below. It was going to rain. Pnin closed the window.

In his own room, on the same floor, he found a note. A laconic wire from Victor had been transmitted by phone: it said that he would be exactly twenty-four hours late.

7

Victor and five other boys were being held over one precious day of Easter vacation for smoking cigars in the attic. Victor, who had a queasy stomach and no dearth of olfactory phobias (all of which had been lovingly concealed from the Winds), had not actually participated in the smoking, beyond a couple of wry puffs; several

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher