![Pnin]()

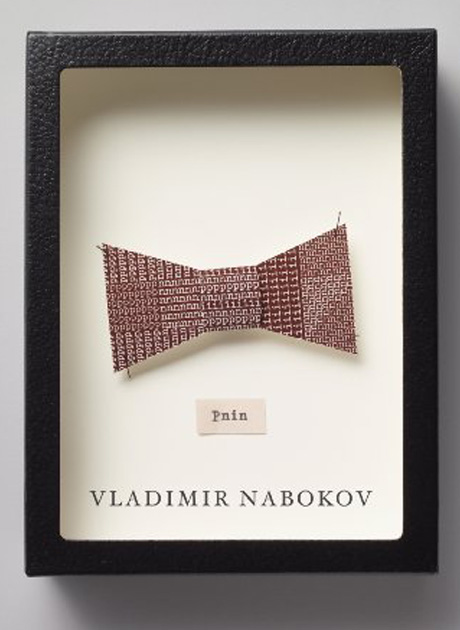

Pnin

himself, looked up, up, up at tall, tall, tall Victor, at his blue eyes and reddish-brown hair. Pnin's well-developed zygomatic muscles raised and rounded his tanned cheeks; his forehead, his nose, and even his large beautiful ears took part in the smile. All in all, it was an extremely satisfactory meeting.

Pnin suggested leaving the luggage and walking one block - if Victor was not afraid of the rain (it was pouring hard, and the asphalt glistened in the darkness, tarnlike, under large, noisy trees). It would be, Pnin conjectured, a treat for the boy to have a late meal in a diner.

'You arrived well? You had no disagreeable adventures?'

'None, sir.'

'You are very hungry?'

'No, sir. Not particularly.'

'My name is Timofey,' said Pnin, as they made themselves comfortable at a window table in the shabby old diner, 'Second syllable pronounced as "muff", ahksent on last syllable, "ey" as in "prey" but a little more protracted. "Timofey Pavlovich Pnin ", which means "Timothy the son of Paul." The pahtronymic has the ahksent on the first syllable and the rest is sloored - Timofey Pahlch. I have a long time debated with myself - let us wipe these knives and forks - and have concluded that you must call me simply Mr Tim or, even shorter, Tim, as do some of my extremely sympathetic colleagues. It is - what do you want to eat? Veal cutlet? O.K., I will also eat veal cutlet - it is naturally a concession to America, my new country, wonderful America which sometimes surprises me but always provokes respect. In the beginning I was greatly embarrassed -'

In the beginning Pnin was greatly embarrassed by the ease with which first names were bandied about in America: after a single party, with an iceberg in a drop of whisky to start and with a lot of whisky in a little tap water to finish, you were supposed to call a grey-templed stranger 'Jim', while he called you' Tim' for ever and ever. If you forgot and called him next morning Professor Everett (his real name to you) it was (for him) a horrible insult. In reviewing his Russian friends throughout Europe and the United States, Timofey Pahlch could easily count at least sixty dear people whom he had intimately known since, say, 1920, and whom he never called anything but Vadim Vadimich, Ivan Hristoforovich, or Samuil Izrailevich, as the case might be, and who called him by his name and patronymic with the same effusive sympathy, over a strong warm handshake, whenever they met: 'Ah, Timofey Pahlch! Nu kak? (Well how?) A vï, baten'ka, zdorovo postareli (Well, well, old boy, you certainly don't look any younger)!'

Pnin talked. His talk did not amaze Victor, who had heard many Russians speak English, and he was not bothered by the fact that Pnin pronounced the word 'family' as if the first syllable were the French for 'woman'.

'I speak in French with much more facility than in English,' said Pnin, 'but you - vous comprenez le

française

Bien? Assez bien? Un peu?'

'Tr ès un peu,' said Victor.

'Regrettable, but nothing to be done. I will now speak to you about sport. The first description of box in Russian literature we find in a poem by Mihail Lermontov, born 1814, killed 1841 - easy to remember. The first description of tennis, on the other hand, is found in Anna Karenina, Tolstoy's novel, and is related to year 1875. In youth one day, in the Russian countryside, latitude of Labrador, a racket was given to me to play with the family of the Orientalist Gotovtsev, perhaps you have heard, It was, I recollect, a splendid summer day and we played, played, played until all the twelve balls were lost. You also will recollect the past with interest when old.

'Another game,' continued Pnin, lavishly sugaring his coffee, 'was naturally kroket. I was a champion of kroket. However, the favourite national recreation was so-called gorodki, which means "little towns". One remembers a place in the garden and the wonderful atmosphere of youth: I was strong, I wore an embroidered Russian shirt, nobody plays now such healthy games.'

He finished his cutlet and proceeded with the subject:

'One drew,' said Pnin, 'a big square on the ground, one placed there, like columns, cylindrical pieces of wood, you know, and then from some distance one threw at them a thick stick, very hard, like a boomerang, with a wide, wide development of the arm - excuse me - fortunately it is sugar, not salt.'

'I still hear,' said Pnin, picking up the sprinkler and shaking his head a little at the surprising

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher