![Ptolemy's Gate]()

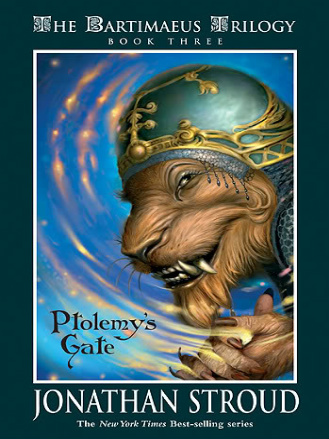

Ptolemy's Gate

understanding. It is true that I am pestered by some of those who have fallen low in fortune. I offer them advice, nothing more. I am just a boy—weak, as you say, and unworldly. I prefer to remain alone, seeking nothing but a little knowledge."

The affectation of humility (for it was affectation— Ptolemy's hunger for knowledge was just as ravenous as the king's son's lust for power, and far more virile) seemed to enrage the prince into a passion. His face grew dark as uncooked meat; little snakes of spittle swayed at the corner of his mouth. "Knowledge, eh?" he cried. "Yes, but of what kind? And to what end? Scrolls and styluses are nothing to a proper man, but in the hands of white-skinned necromancers they can be deadlier than the strongest iron. In old Egypt, they say, eunuchs mustered armies with the stamp of a foot and swept the rightful pharaohs into the sea! I don't intend that to happen to me. What are you smirking about, slave?"

I hadn't meant to smile. It's just I enjoyed his account, having been in the vanguard of the army that did the sweeping, a thousand years before. It's good when you make an impression. I bowed and scraped. "Nothing, master. Nothing."

"You smirked, I saw you! You dare laugh at me—the king-in-waiting!"

His voice quivered; the soldiers knew the signs. Their pikes made small adjustments. Ptolemy uttered placatory noises: "He did not intend offense, my lord. My scribe was born with an unfortunate facial tic, a grimace that in harsh light can seem a baleful smirk. It is a sad affliction—"

"I will have his head stuck above the Crocodile Gate! Guards—"

The soldiers lowered their pikes, each keener than the rest to drench the stones with my blood. I waited meekly for the inevitable.[3]

[3] i.e. a whirlwind of slaughter. Carried out by me.

Ptolemy stepped forward. "Please, cousin. This is ridiculous. I beg you—"

"No! I will hear no argument. The slave will die."

"Then I must tell you." My master was suddenly very close to his brutish cousin; he seemed somehow taller, his equivalent in height. His dark eyes gazed directly into the other's watery ones, which squirmed in their sockets like a fish upon a spear. The king's son quailed and shrank from him; his soldiers and attendants shifted uneasily. The sun's warmth dimmed; the courtyard grew cloudy. One or two of the soldiers had goose pimple s on their legs. "You will leave him alone," Ptolemy said, his voice slow and clear. "He is my slave, and I say he deserves no punishment. Leave with your lackeys and return to your wine vats. Your presence here disturbs the scholars and brings no credit on our family. Your insinuations likewise. Do you understand?'"

The king's son had bent so far back to avoid the piercing stare that half his cape dragged on the ground. He made a noise like a marsh toad mating. "Yes," he croaked. "Yes."

Ptolemy stepped away. Instantly he seemed to dwindle; the darkness that had gathered around the little group like a winter cloud lifted and was gone. The onlookers relaxed. Priests rubbed the backs of their necks; nobles exhaled noisily. A midget peeped out from behind a wrestler.

"Come, Rekhyt." Ptolemy repositioned the scrolls under his arm and glanced at the king's son with studious disinterest. "Good-bye, cousin. I am late for lunch."

He made to step past. The king's son, white-faced and tottering, uttered an incoherent word. He lurched forward; from beneath his cloak a knife was drawn. With a snarl, he lunged at Ptolemy's side. I raised a hand and gestured: there was a muffled impact, as of a masonry block landing on a bag of suet pudding. The king's son doubled over, clutching his solar plexus, mouth bubbling, eyes popping. He sank to his knees. The knife dropped impotently on the stones.

Ptolemy kept walking. Four of the soldiers sprang to uncertain life; their pikes went low, they made aggressive sounds. I swept my hands in a semicircle; away they flew, one after the other—head first, toes last, out across the courtyard cobbles. One hit a Roman, another a Greek; a third skidded a yard upon his nose. The fourth crashed into a trader's stand and was half buried by an avalanche of sweetmeats. They lay outstretched like points upon a sundial.

The others in the group were chicken. They cowered together and made no move. I kept close watch upon the old bald priest, though—I could see he was tempted to do something. But he met my eyes and decided it was best to live.

Ptolemy kept walking. I

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher