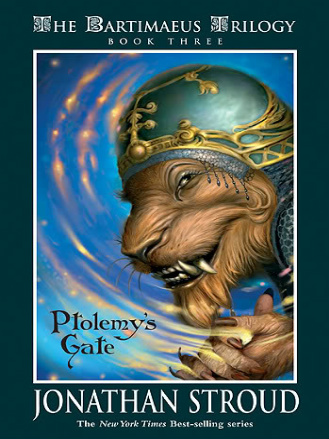

![Ptolemy's Gate]()

Ptolemy's Gate

one.

That morning, as on every morning, the list of complaints, wrongs, and outright woes was recited and considered. To some, advice was given. To a few (the more obviously covetous or deluded), help was refused. To the rest, action of one sort or another was promised and delivered. Imps and foliots departed through the windows and flitted out across the city on a variety of errands. A certain noble djinni was seen to leave and, in due course, return. For several hours a steady stream of spirits came and went. It was a very busy household.

At half-past eleven the doors were shut and locked for the day. Thereafter, by a back route (to avoid lingering petitioners, who would have delayed him), the magician Ptolemy departed for the Library of Alexandria to resume his studies.

We were walking across the courtyard outside the library building. It was lunchtime and Ptolemy wished to get anchovy bread in the markets on the quay. I strolled beside him as an Egyptian scribe, bald-headed, hairy of leg, busily arguing with him on the philosophy of worlds.[1] One or two scholars passed us as we went: disputatious Greeks; lean Romans, hot of eye and scrubbed of skin; dark Nabataeans and courteous diplomats from Meroe and far Parthia, all here to drink knowledge from the deep Egyptian wells. As we were about to leave the library compound, a clash of horns sounded in the street below. Up came a little knot of soldiers, the Ptolemaic colors aflutter on their pikes. They drew apart to reveal Ptolemy's cousin, the king's son and heir to the throne of Egypt, slowly swaggering up the steps. In his train came an adoring cluster of favorites— toadies and fawners to a man.[2] My master and I stopped; we inclined our heads in the traditional manner of respect.

[1] He claimed that any connection between the two must be for a purpose: it was the job of magicians and spirits to work toward a closer understanding of what this purpose was. I regarded this (politely) as utter balderdash. What little interaction there was between our worlds was nothing but a cruel aberration (the enslavement of us djinn), which should be terminated as soon as possible. Our argument had become heated, and earthy vulgarities were avoided only by my concern for rhetorical purity.

[2] They included senior priests, nobles of the realm, flophouse drinking partners, professional wrestlers, a bearded lady, and a midget. The king's son had a jaded appetite and broad tastes; his social circle was wide.

"Cousin!"The king's son lolled to a stop; his tunic was tight about his stomach, wet where the brief walk had drawn sweat from his flesh. His face was blurry with wine, his aura sagged with it. His eyes were dull coins under their heavy lids. "Cousin," he said again. "Thought I'd pay you a little visit."

Ptolemy bowed again. "My lord. It is an honor, of course."

"Thought I'd see where you skulk away your days instead of staying at my side"—he took a breath—"like a loyal cousin should." The toadies tittered. "Philip and Alexander and all my other cousins are accounted for," he went on, tumbling over the words. "They fight for us in the desert, they work as ambassadors in principalities east and west. They prove their loyalty to our dynasty. But you. . ." A pause; he picked at the wet cloth of his tunic. "Well. Can we rely on you?"

"In whatever way you wish me to serve."

"But can we, Ptolemaeus? You cannot hold a sword or draw a bow with those girlish arms of yours; so where's your strength, eh? Up here" —he tapped his head with an unsteady finger—"that's what I've heard. Up here. What do you do in this dismal place then, out of the sun?"

Ptolemy bowed his head modestly. "I study, my lord. The papyri and books of record that the worthy priests have compiled, time out of mind. Works of history and religion—"

"And magic too, by all accounts. Forbidden works." That was a tall priest, black-robed, head shaven, and with white clay daubed faintly around his eyes. He spat the words out softly like a cobra shooting venom. He was probably a magician himself.

"Ha! Yes. All manner of wickednesses." The king's son lurched a little closer; sour fumes hung about his clothes and issued from his mouth. "The people celebrate you for it, cousin. You use your magic to beguile them, to win them over to you. I hear they come daily to your house to witness your devilry. I hear all kinds of stories."

Ptolemy pursed his lips. "Do you, my lord? That is beyond my

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher