![Ptolemy's Gate]()

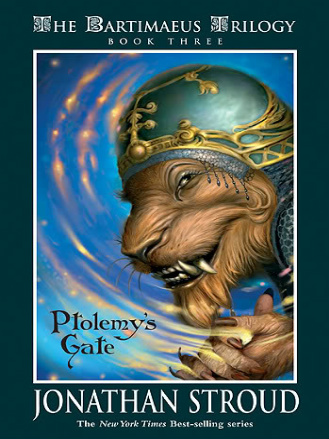

Ptolemy's Gate

"Yes?"

"Might I have a word?" He had chosen to wear a more official suit than was his wont. He hadn't needed to do this exactly, but he'd found he wanted to make the best impression. Last time she'd seen him, he'd been nothing but a humiliated boy.

"What do you want?"

He smiled. She was very defensive. Goodness knows what she thought he was. Some official, come to inquire about her taxes . . ."Just a chat," he said."I recognized you. . . and I wondered if. . . if you recognized me."

Her face was pale, still etched with worry; frowning, her eyes scanned his. "I'm sorry," she began, "I don't— Oh. Yes, I do. Nathaniel. . ." She hesitated. "But I don't suppose I can use that name."

He made an elegant gesture. "It is best forgotten, yes."

"Yes. . ." She stood looking at him—at his suit, his shoes, his silver ring, but mostly at his face. Her scrutiny was deeper than he had expected, serious and intense. Rather to his surprise, she did not smile, or display any immediate elation. But of course his appearance had been sudden.

He cleared his throat. "I was passing. I saw you and—well, it's been a long time."

She nodded slowly. "Yes."

"I thought it would. . . So how are you, Ms. Lutyens? How are you keeping?"

"I'm well," she said, and then, almost sharply: "Do you have a name I am allowed to use?"

He adjusted a cuff, smiled vaguely. "John Mandrake is my name now. You may perhaps have heard of me."

She nodded again, expressionless. "Yes. Of course. So, you're doing. . . well."

"Yes. I'm Information Minister now. Have been for the last two years. It was quite a surprise, as I was rather young. But Mr. Devereaux decided to take a gamble on me and"—he gave a little shrug—"here I am."

He had expected this to elicit more than yet another brief nod, but Ms. Lutyens remained uneffusive. With slight annoyance in his voice, he said, "I thought you'd be pleased to see how well it's all turned out, after—after the last time we saw each other. That was all very . . . unfortunate."

He was using the wrong words, that much he could tell— slipping into the studied understatement of his ministerial life rather than saying exactly what was in his mind. Perhaps that was why she seemed so stiff and unresponsive. He tried again: "I was grateful to you, that's what I wanted to tell you. Grateful then. And I still am now."

She shook her head, frowning. "Grateful for what? I didn't do anything."

"You know—when Lovelace attacked me. That time he beat me, and you tried to stop him. . . I never got a chance to—"

"As you say, it was unfortunate. But it was also a long time ago." She flicked a wisp of hair from her face. "So, you're the Information Minister? You're the one responsible for those pamphlet things they're giving out at the stations?"

He smiled modestly. "Yes. That's me."

"The ones that tell us what a fine war we're waging and how only the best young men are signing up for it, that it's a man's job to sail off to America and fight for freedom and security? The ones that say that death is a fit price to pay for the survival of the Empire?"

"A trifle too succinct, but that's the thrust of it, I suppose."

"Well, well. You've come a long way, Mr. Mandrake." She was looking at him almost sadly.

The air was cold; the magician stuffed his hands in his trouser pockets and glanced up and down the road, searching for something to say. "I don't suppose you usually see your pupils again," he said. "When they've grown up, I mean. See how they've got on . . ."

"No," she agreed. "My job is with the children. Not with the adults they become."

"Indeed," He looked at her battered old bag, remembering its dull satin interior, with the little cases of pencils, chalks, ink pens, and Chinese brushes. "Are you happy in your job, Ms. Lutyens?" he asked suddenly. "I mean, happy with your money, and your status and all that? I ask you because I could, you know, find you other employment if you chose. I have influence, and could find you something better than this. There are strategists in the War Ministry, for example, who need people with your expertise to design mass-produced pentacles for the American campaign. Or even in my ministry—we've created an advertising department to better put across our message to the people. Technicians like you would be welcomed. It's good work, dealing with confidential information. You'd get a rise in status."

"By 'the people,' I take it you mean 'commoners'?" she asked.

"That's what

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher