![Ptolemy's Gate]()

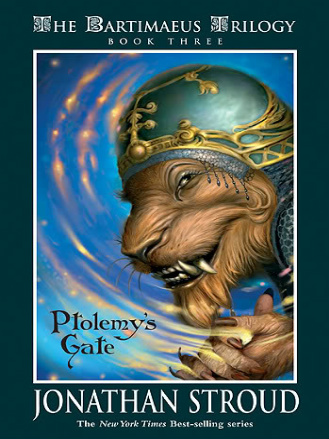

Ptolemy's Gate

that it was so; the notion coiled and slithered deep inside him.

If the motive for the djinni's lie was hard to fathom, the timing of the revelation could not have been more bitter, coming so soon after Mandrake had jeopardized his career to save his servant's life. His eyes burned as he recalled the act; his folly rose up to choke him.

In the midnight solitude of his study he made the summons. Twenty-four hou rs had passed since he had dismissed the frog; whether Bartimaeus's essence would have healed by now he did not know. He no longer cared. He stood ramrod-stiff, hands drumming incessantly on the desk before him. And waited.

The pentacle remained cold and quiet. The incantation echoed in his head.

Mandrake moistened his lips. He tried again.

He did not make a third attempt, but sat down heavily in his leather chair, seeking to suppress the panic that rose within him. There could be no doubt: the demon was already in the world. Someone else had summoned him.

Mandrake's eyes burned hot into the darkness. He should have predicted this. One of the other magicians had disregarded the risk to the djinni's essence and had sought to find out what he knew about the Jenkins plot. It hardly mattered who it was. Whether Farrar, Mortensen, Collins, or another, the outlook for Mandrake was grim indeed. If Bartimaeus survived, he would doubtless tell them Mandrake's birth name. Of course he would! He had already betrayed his master once. Then his enemies would send their demons, and he would die, alone.

He had no allies. He had no friends. He had lost the support of the Prime Minister. In two days, if he survived, he would be on trial before the Council. He was on his own. True, Quentin Makepeace had offered his support, but Makepeace was quite probably deranged. That experiment of his, that writhing captive. . . the memory of it repelled John Mandrake. If he managed to salvage his career, he would take steps to stop such grotesque activities. But that was hardly the priority now.

The night progressed. Mandrake sat at his desk, thinking. He did not sleep.

With time and weariness, the troubles that beset him began to lose their clarity. Bartimaeus, Farrar, Devereaux, and Kitty Jones, the Council, the trial, the war, his endless responsibilities—everything merged and flickered before his eyes. A great yearning rose in him to cast it all off, remove it like a wet and fetid set of clothes, and step away, if only for a moment.

A thought occurred to him, wild, impulsive. He brought out his scrying glass, and ordered the imp to locate a certain person. It did so swiftly.

Mandrake rose from his chair, conscious of the strangest feeling. Something dredged from the past—almost a sorrow. It discomforted him, but was pleasant too. He welcomed it, though it made him uneasy. Above all, it was not of his current life—it had nothing to do with efficiency or effectiveness, with reputation or with power. He could not rid himself of the desire to see her face again.

First light: the skies were leaden gray and the pavements dark and sloughed with leaves. The wind skittered through the branches of the trees and around the stark spire of the war memorial in the center of the park. The woman's coat was turned up against her face. As she approached, striding swiftly along beside the road, head down, hand up against her scarf, Mandrake failed to recognize her at first. She was smaller than he recalled, her hair longer and a little flecked with gray. But then from nowhere, a familiar detail: the bag she carried her pens in—old, battered, recognizably the same. The same bag! He shook his head in wonder. He could buy her a new one— a dozen of them—should she wish it.

He waited in the car until she drew almost level, uncertain until the last moment whether he would actually step out. Her boots scattered the leaves, tripped carefully around the deeper puddles, walking speedily thanks to the cold and the moisture in the air. Soon she would be past him. . .

He despised himself for his hesitation. He opened the roadside door, got out, and stepped across to intercept her.

"Ms. Lutyens."

He saw her give a sudden start and her eyes dart around to appraise him and the sleek, black car parked behind. She walked another two hesitant steps, came to an uncertain halt. She stood looking at him, one arm hanging limply at her side, the other clutching at her throat. Her voice, when it came, was small—and, he noted, rather scared.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher