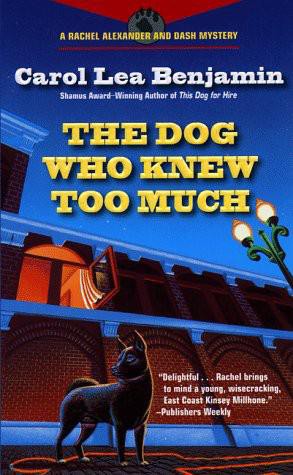

![Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much]()

Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much

I had a strong feeling that she’d been murdered?

You mean an intuition ? Marty might ask.

Or would he say, “Handwriting analysis? Pretty flaky, Rachel, even for you. What’s next, a Ouija board?”

Just thinking about it, I could almost hear them snickering.

No way. If their motto was Cover your ass, well, so was mine. I didn’t need to be thought a fool by my local branch of New York ’s finest.

What, after all, did I have so far? Cops say the criminal always leaves something of himself at the scene, and that he always takes something away from the scene when he leaves. Could the note, written for another reason, be what was left? That could mean the killer had planned Lisa’s death. So what might he have taken away? A hair? A thread? The scent of her perfume? But so what? Whatever he took, whatever he left, a fingerprint, some dandruff, even his damn wallet, couldn’t he have been leaving things and taking things away from the scene for years? After all, he had the keys. Didn’t he?

Or she?

It was way too soon to talk to the cops. All I had was Lisa’s note. And the nagging idea that its purpose had been universally misconstrued.

12

Are You Seeing Anyone?

IN THE EVENING I walked Dash to where the car was parked and drove to Rockland County to visit my sister. Maybe there I’d discover something telling, like if my sister’s husband had suddenly started wearing turtlenecks to cover up the hickeys on his lousy, philandering neck.

I made a mental note. Check bald spot for signs of hair transplants in progress. Check bathroom for Grecian Formula for Men. Get Lillian talking.

The gate was open, and I parked just outside the two-car garage. What a different life from mine my sister had—two children, an expensive suburban house, a fully stocked and equipped kitchen, a washer and a dryer, even a freezer. And now, or so it appeared, a cheating husband.

I walked down the long, skinny deck. The door was ajar. I called Lili’s name and walked in. She was in the kitchen making soup, her sleeves rolled up, the chopping board deep in carrots, celery, parsley, and parsnips, a cut-up chicken in a bowl to her right.

“Oh, I didn’t hear you,” she said, her face without makeup, her hair uncombed and sticking out around her face as if she’d stuck her finger in a socket. She was wearing one of Ted’s old shirts and what we used to call fat pants, baggy, wide-legged jeans. Maybe those were Zachery’s. She had a dishcloth tucked into her waist with assorted stains in various colors on it, and she wore fuzzy slippers, black-and-white ones, in the shape of pandas. If not for the size of her feet, eleven, I would have thought the slippers were Daisy’s.

I thought about Lisa’s mother, perfect in her gray silk dress and simple pumps. My sister used to dress like that, fussing with her hair, wearing makeup and pretty clothes even when she was staying home. Then I thought about the blond and wondered what difference dressing up would make anyway.

Lili held her arms out to the side as I hugged her, so as not to get raw veggies on Lisa’s gorgeous clothes. Since she always complained about the way I looked, I thought she’d notice the improvement. But she didn’t. She just turned back to the cutting board and resumed her chopping.

“Zachery is bowling,” she said, as if I’d asked. “Daisy is sleeping over at Stephanie’s. Teddy had to go in to the city and take care of something at work this afternoon. Inventory? Was that what he said? Whatever. So it’s just the two of us.” She looked up now and flashed me a Kaminsky grin.

“Are you hungry? There’s cold chicken in the fridge. Make some tea for us, too.”

I filled the kettle and lit the stove, watching as the blue flames momentarily fogged the pot.

“I thought Ted would be home for dinner.” Lillian shrugged. “He’s such a workaholic, that man. You know, I thought he’d get better as he got older, but he’s worse. ” She stopped cutting and looked at me. “Sometimes I worry that something’s wrong,” she said. She turned back to the cutting board and carefully began taking the skin off a clove of garlic.

“What do you mean ? ” I asked, feeling as if I hadn’t taken a breath since Nixon made his Checkers speech.

“Like if the business is in trouble and Ted won’t say. He’s so good, Rachel. He’s never wanted me to worry about our finances.” She began to peel another clove.

I took two mugs off the shelf, put a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher