![Right to Die]()

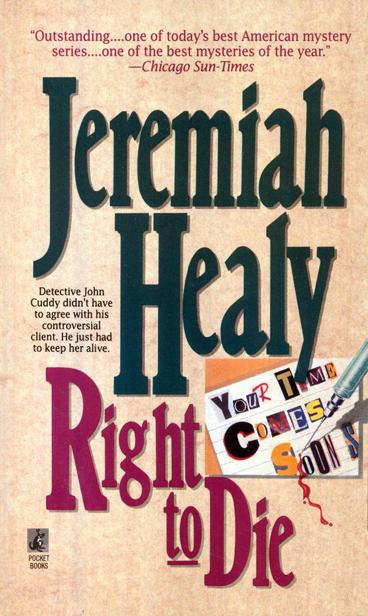

Right to Die

alternating wings each time the feathers grow back, you can let them out in the yard or whatever, because they can’t fly. Be like a heliocopter with a bum tail rotor, just spiral down to the ground. But I couldn’t bring myself to do that to her, seems like mutilation to me. So I just make sure to keep her in the house with the spacelock. Put that up myself.”

To be polite, I turned in my chair to admire the patchwork job Doleman had done in framing a second, inner door at the entrance to form his spacelock.

Turning back, I said, “Sensible. Mr. Doleman—”

“Be crazy to have her outside anyway. With a bum wing, she’d be a sitting duck for cats, dogs, what have you. Used to hunt every chance I’d get, deer in the fall, waterfowl in the spring. Never would take a stationary bird, but I can’t say that about a lot of fellows I met. No sense of sport in them. The hell good is it to hunt, you don’t do it for the sport?”

“Not much.”

“You bet not much. Marpessa here is friendly as a spaniel pup. Comes when she’s called, doesn’t crap the furniture or rug, just does this little sideways dance, lets me know it’s time for her to go.”

I could hardly wait.

“ ‘Course, she’s got her dark side too. Costs an arm and a leg this far north to keep her warm enough. And she gets real jealous if there are any kids... around...” Doleman seemed to stall, like a motor that was doing fine until someone shifted to drive. His lips moved convulsively, as though he were practicing puckering.

“Mr. Doleman?”

He revived. “She’ll talk your ear off too. Even think she understands some of it. She’ll hang upside down from a rope I got in the kitchen there, and she’ll say, ‘Look, look,’ like a little kid...”

Again the stalling effect.

I repeated his name.

This time Doleman barely came out of the daydream.

“What was it you wanted?”

“I’m doing some work on the debate at the Rabb the other night.”

“The Rabb?”

“The library. When you asked that professor a question?”

“Oh.” Doleman lowered his head, shaking it. Marpessa transferred all her weight to the left foot, using her beak to pick at the claws on the right one. In a clearer tone of voice he said, “Well, go ahead.”

“I got the impression from what you said to Professor Andrus that you felt she was involved in your daughter’s death.”

“Not involved. Responsible. There’s a difference.” Now he was more the man I’d seen rise from his seat at the debate. Staunch, certain.

“Mr. Doleman, can you tell me what happened?”

“I can. You have time to hear it?”

“Yes.”

Doleman moved his hands as though lathering them with soap. “Heidi was my daughter. Wasn’t the name I would have picked out for her, but she was an orphan, war orphan out of Germany . The wife and I couldn’t have children ourselves, so we jumped at the chance to raise her.”

As Doleman talked, I did some arithmetic. “What happened to your daughter?”

“Once we got her over here—stateside, I mean—she was fine. Oh, some nightmares sure, and she couldn’t abide loud noises, probably reminded her of the bombs. And she was shy around strangers, just like Marpessa here.” Doleman ruffled the bird’s feathers, and Marpessa pecked him lightly on the left cheek. “But she did just great in school, lost most of the accent, went on to be a secretary downtown.”

“When was this, Mr. Doleman?”

“When was what?”

“When she became a secretary.”

“Oh. Just after they shot Jack Kennedy. She had to start back a couple of grades in school, on account of having no schooling, much less any English, back in the old country. But she was a good girl, no trouble with boys or anything. Then—”

He stopped again, but I didn’t prompt him.

“Then the wife— Florence —had the heart attack. It just come on her one night, no warning at all. Heidi was a godsend, taking care of the house for me while I finished up at the MTA—I was a motorman, Arborway line mostly. They call it the MBTA now, but not me. After I retired, Heidi and me were going to sell this place, move some-wheres warm, but we never got around to it.”

“How old was Heidi when your wife died, Mr. Doleman?”

“How old?”

“Yes.”

“Oh, out of her teens for sure. Hard to say. See, she didn’t give us any trouble like most kids do, so you didn’t pay that much attention to how old she was. She always seemed older, what she’d been through

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher