![Right to Die]()

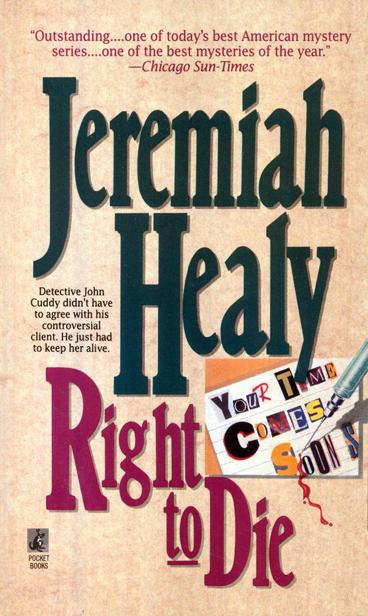

Right to Die

fell into our waitress and eggs Benedict.

= 3 =

“John, you working out formal now?”

Gesturing at my coat and tie, Elie put his Dunkin’ Donuts coffee on the front desk. His olive skin and blue eyes were twin legacies from the broad gene pool in Lebanon . Maybe twelve people were using the Nautilus machines in the large room behind him, a separate aerobics class thumping in the back studio.

“I was in yesterday, Elie. You got a minute?”

“Sure, sure. How can I help you?”

I waited for a heavyset man in a Shawmut Bank T-shirt to dismount the Lifecycle closest to the desk and head for the showers.

“Not for publication, but I’m thinking about running the marathon.”

A look of concern. “ Boston ?”

“Right.”

“You still doing what, three to five miles?”

“Three times a week. Most weeks, anyway.”

“John, I’m not a runner, but if I was as big as you, I wouldn’t try it.”

“Why not?”

“Running is awful tough on the joints over the longer distances. Your size and weight, there’s going to be a lot of stress on the knees, hips, even the ankles.”

“Can’t I train for that?”

“I don’t think you can train without that. But like I said, I’m not a runner, and unfortunately, nobody on the staff here is. Biking and rowing, sure. But the marathon? No.”

“How can I find somebody?”

“You mean like to train you? That costs a fortune. Tell you what. I can go through some magazines at the library.”

“Magazines?”

“Yeah, like Runner’s World, that kind of thing. They got to have an article on doing your first marathon.”

“Elie, I don’t want you to go to any trouble.”

“No trouble, really. They’re all out in the open, second floor.”

“Elie, thanks but no. I can check the library on my own. Any other suggestions?”

The concerned look again. ^’Friend to friend?”

“Yes.”

“Don’t do it.”

“Did Nancy get to you?”

“ Nancy who?”

“Never mind.”

By the time I left Elie, it was pretty sunny, so I walked downtown along Commonwealth Avenue. Commonwealth begins at the Public Garden and rambles forever westward. Over the first ten blocks, a wide center strip hosts civic statues and grand Dutch elms that so far have survived both the disease and occasional hurricanes. With a dusting of snow, my route would have been a postcard.

Midway through the Public Garden , I stopped on the bridge spanning the Swan Pond. In warmer weather the city raises the water level to provide* swan boat rides. In colder weather the city lowers the water level to form a rink. Tourists with cameras, many of them Asian, stood at the edges of the ice, taking pictures of some locals playing pick-up hockey. None of the skaters was very good, but Boston does have the knack of creating photo ops at every time of the year.

Crossing Charles Street , the Common was bleaker, as usual. Centuries ago, the site really was used in common by farmers for grazing their livestock. Now the three-card-monte dealers and souvenir wagons had flown south for the winter, replaced by raggedy runaways hopeful of peddling themselves for a warm bed and manageable abuse. Further on, groups of three or four men stood around benches, glancing in every direction while gloved hands traded glassine envelopes or plastic vials for folded currency.

My office was in a building on Tremont, near the Park Street subway station. Derelicts clustered in irregular patterns around the entrances to the station, grateful for the canned heat from below and the solar variety from above. A few jerked up their heads as they became aware of how close I would come to them. I looked away to calm their fears of being rousted.

There used to be a lot of pigeons on the Common. Now there are a lot of homeless people and not so many pigeons. You figure it out.

I used my key to get into the building, taking the elevator up to my office. On a piece of paper I wrote, “Cuddy, ring bell” and drew an arrow underneath. Back downstairs, I taped the directions to the glass door. Then I returned to the office to kill some time and paperwork, waiting for two o’clock.

They made a striking pair, if not quite a couple.

Alec Bacall (“Call me Alec, please”) was as tall as I am but slim, with a ramrod posture and a steel-clamp handshake to go with the steel-trap mind. Pushing forty, his hair was still the color of wheat and probably streaked toward platinum if he spent much time outdoors in the summer. The Prince

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher