![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

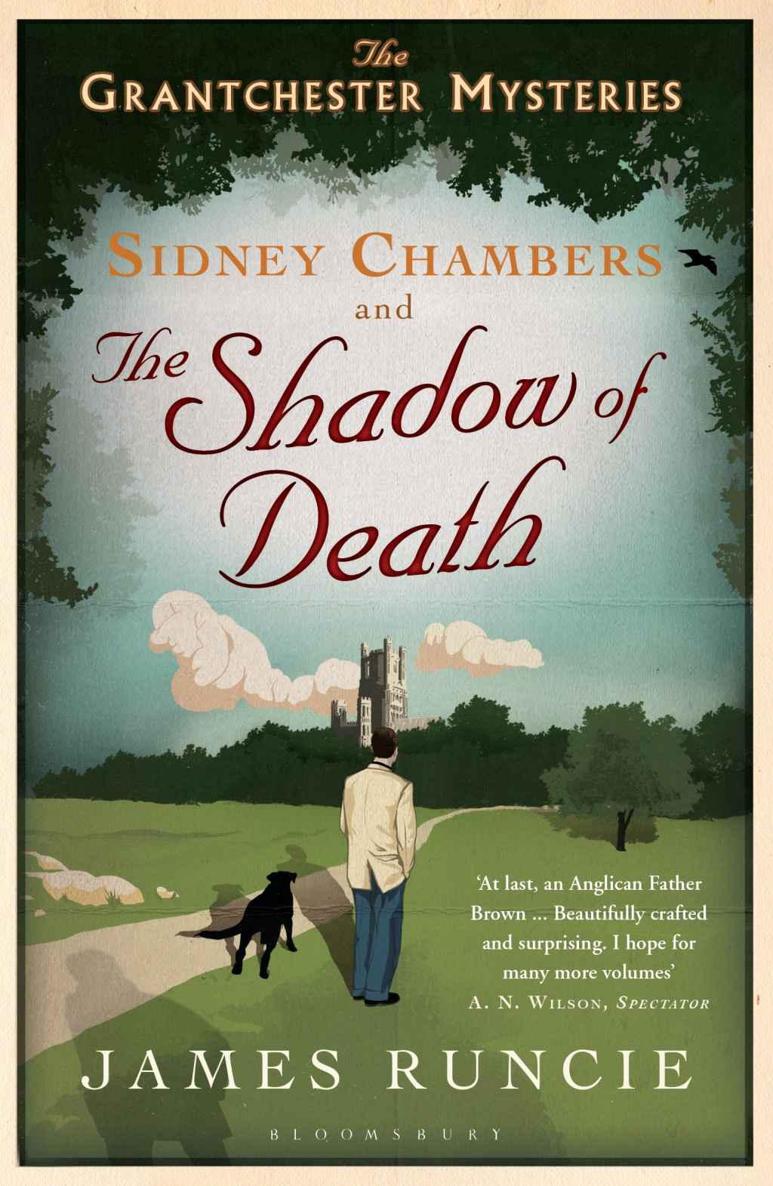

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

allow me to keep this note so that I can show it, in confidence, to my friend Inspector Keating in order to set his mind at rest. As soon as I have done so, then I will return it. May I have your permission to do this? I can assure you that the information would remain confidential.’

‘I won’t get into trouble, will I?

‘I think that is unlikely. The police are convinced Mr Staunton died by his own hand and this note appears to prove it.’

‘Appears? It states it quite clearly.’

‘Indeed it does,’ Sidney admitted. ‘And so I am sure that it will be returned to you shortly. The only strange thing is why it has come to light now.’

‘I explained. It is private. I was upset. And it is mine. Meant only for me.’

Sidney realised that he would have to give Inspector Keating the note and accept the reality of what had happened. All that he had been doing was to complicate a straightforward case and arouse doubt. He should never have listened to Pamela Morton’s suspicions or been railroaded by her charm. Clearly the pressure of the infidelity had been too much for Stephen Staunton and he had taken the only escape route that he could find.

And yet, for reasons he could not quite fathom, Sidney’s suspicions would not abate. Why, for example, would Stephen Staunton leave a note for his secretary but not for his wife? What made Miss Morrison so hesitant to provide the police with information? And who had replaced the whiskey in the office?

Annabel Morrison looked him in the eye. ‘Please return the note as soon as you can.’

‘Of course.’

‘I hope you can understand how distressing this has been, Canon Chambers . . .’

‘I can, Miss Morrison. It has been distressing for everyone.’

‘I am glad you understand that. Good day, Canon Chambers.’

Sidney closed his front door and made his way back into the hall. He was still holding the note. He looked down but could not focus on the words. And then, unbidden, he imagined Stephen Staunton’s widow, Hildegard, sitting alone with her porcelain figures, due to receive Christmas cards from people who did not yet know that her husband was dead.

The following Sunday, having attended the last, and the shortest, Communion service before lunch, Pamela Morton knocked on the vicarage door. She was dressed in a dark navy coat with a wide-brimmed saucer hat that looked extraordinarily formal, even for church. She informed Sidney that she would take a very small whisky but could not stay long. She was expected for lunch at Peterhouse. A driver was waiting.

Once she had sat down her impatience was revealed. ‘I am rather disappointed in you, Canon Chambers,’ she began, her voice altogether more strident than Sidney had remembered. ‘I was hoping that you might have something for me by now. Have you found anything at all?’

‘A little,’ Sidney answered. Despite the imperious charms of his guest, his attitude to her plight had cooled since his meeting with Hildegard Staunton. If any one person involved in this sorry business required his time and sympathy it was surely the widow rather than the mistress.

‘Then what have you discovered?’ Pamela asked.

‘I am afraid that, despite my endeavours, your suspicions of foul play are going to be difficult to prove. Stephen Staunton left a note.’

‘Do you have it?’

‘I do.’

‘Can I see it?’

Sidney crossed over to his desk and handed the piece of paper to the dead man’s mistress. He knew that this was a breach of Miss Morrison’s privacy and that he should have taken the evidence straight to the police as he had promised but he wanted to see what Pamela Morton had to say.

She was less interested than he had hoped. In fact she was unimpressed. ‘No date, I see.’

Sidney was almost irritated by her dismissal of the only fact he had uncovered. ‘It is Stephen Staunton’s handwriting, is it not?’

‘It is . . .’

‘You hesitate to accept it as genuine.’

Pamela Morton was thinking. ‘His secretary could just as well have written it. She certainly knew how to forge his signature.’

‘How do you know that?’

‘Stephen told me. It was a tacit agreement between them. He let her go home early on Wednesday afternoons – I think she saw her mother – and then, on other days, if he had to leave before she had finished his letters, he would trust her to read them through and dash off his signature. It gave him more time to see me, he said, and then he could get home

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher