![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

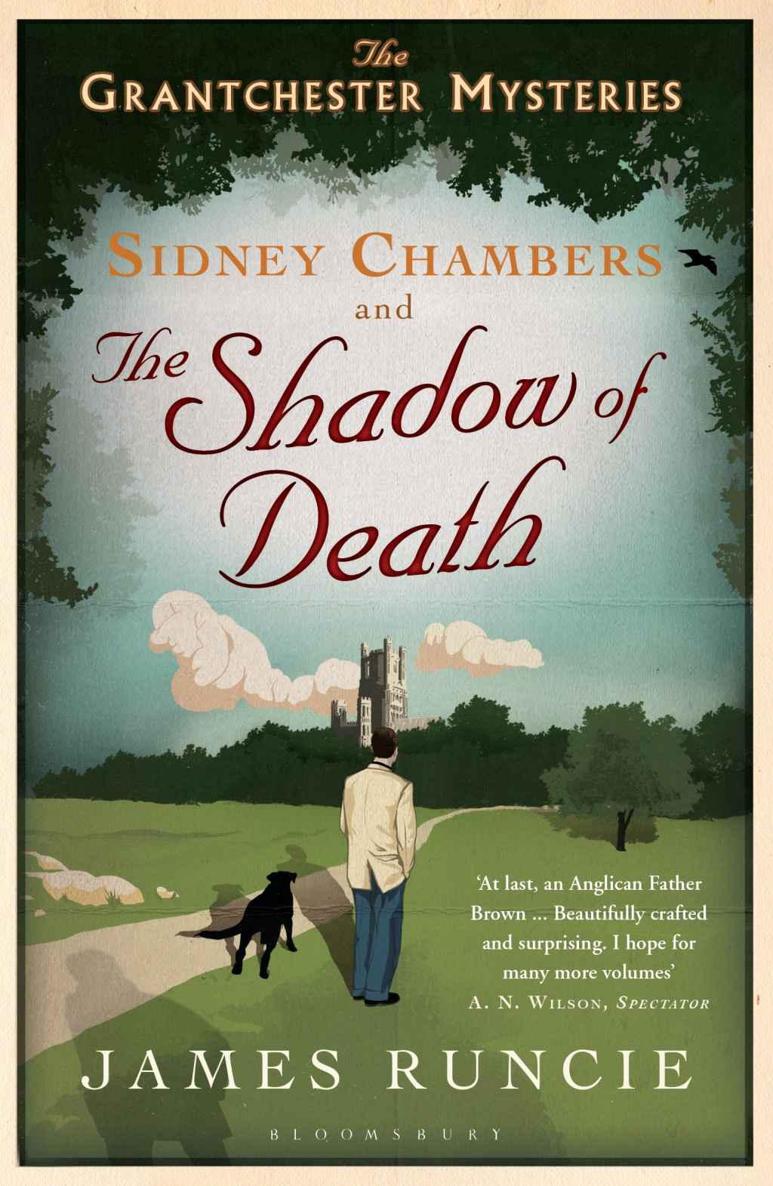

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

would sleep anywhere?’ Sidney asked.

‘It was a routine. At two o’clock every day. His last appointment ended every morning at 12.30. Lunch. Sleep. And then his next appointment would be at 3.15. He was like a machine. He could sleep through anything. A bomb could go off and he would not notice. I sometimes worried that if he was ever driving the car at two o’clock he would fall asleep, crash the car and kill himself. In the end he did not need a car to do that for him . . .’

Sidney leafed through the diary. There didn’t seem to be anything of note but perhaps, he wondered, he could examine it more closely at home, when he had more time. Then he might be able to work out what had been erased. ‘Do you mind if I borrow this?’ he asked.

‘There is nothing to see.’

‘I would like to think about it a little more. It might be the basis of a sermon, perhaps; the disappearance of the days . . .’

‘For they are as grass.’

Sidney had a sudden memory. ‘ Denn alles Fleisch, es ist wie Gras. Brahms’s German Requiem .’

‘You know it?’

‘I heard it in Heidelberg, just after the war. I found it very moving: the singing in unison at the start of the second movement, the journey from pain to comfort.’

‘It was popular all over Germany. It was like a death march.’

Sidney was still holding the diary. ‘I know this must have a sentimental value.’

‘We were not sentimental people.’

‘I’m not sure that I agree with you. Your husband remembered your birthday and, it seems, your wedding anniversary.’

‘He was good about those things. It was easy for him to remember. Then he could feel confident. He was a kind man who wanted to please people. I could not help him as much as I wanted to. I should have been a better wife.’

‘You must not blame yourself.’

‘How can I not? My husband took his own life.’

‘But he must have had friends?’

‘You came to the funeral. They were there. But we did not socialise. My husband did not enjoy the politeness of dinner parties. He did not like being forced to behave well. He preferred to see people on their own . . .’

‘And out of office hours?’

‘I did not mind who my husband saw. I did not ask questions. He was kind to me. We had this house. We had food. I was warm. And I could play the piano as much as I liked without being disturbed. It was not complicated. All I wanted in my life was someone to be kind to me and I found him. We were not happy all the time but I do not think we were ever sad. Now, of course, this has gone . . .’

Sidney wondered if Hildegard was about to cry and then realised that it was he who was on the verge of tears. He felt immense pity and yet he could not think how to express it or give her comfort. ‘You have your memories,’ he said quietly.

‘Yes, of course.’ Hildegard Staunton tried to accept Sidney’s cliché. ‘I have my memories. Not that all of them are good. And now I have to start again.’

‘If there’s anything I can do?’

Sidney knew that his offer was weak but he was surprised by the alacrity of Hildegard Staunton’s response. ‘You can pray for me, Canon Chambers. That would be helpful. And you can pray for my husband too. I would like to know that you are doing that; that someone will care for us. You know that some believe that people who take their own life will never go to heaven?’

‘I am not one of those people,’ said Sidney. ‘And it is not for me to judge. We live as we can. If we cannot meet our hopes and expectations, then we fall short. It is, if you will forgive me, part of being a Christian. We are not as we might be . . .’

Hildegard gave Sidney the faintest of smiles. ‘Is that not a very long way of saying that nobody is perfect?’

‘It is,’ said Sidney. ‘Perhaps you should be a priest yourself . . .’

‘Oh, I don’t think that would be allowed.’

‘You could be a deaconess . . .’

‘Now you are teasing me . . .’

‘I like to see you smile,’ said Sidney, boldly.

‘And I like it that you make me smile,’ Hildegard replied.

One of the advantages of being a clergyman, Sidney decided, was that you could disappear. Between services no one quite knew where you were, who you might be visiting, or what you might be doing: and so, on most Mondays, his designated day off, he would bicycle a few miles out of town, ride out through the village lanes of Trumpington and Shelford, and then take the Roman Road for

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher