![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

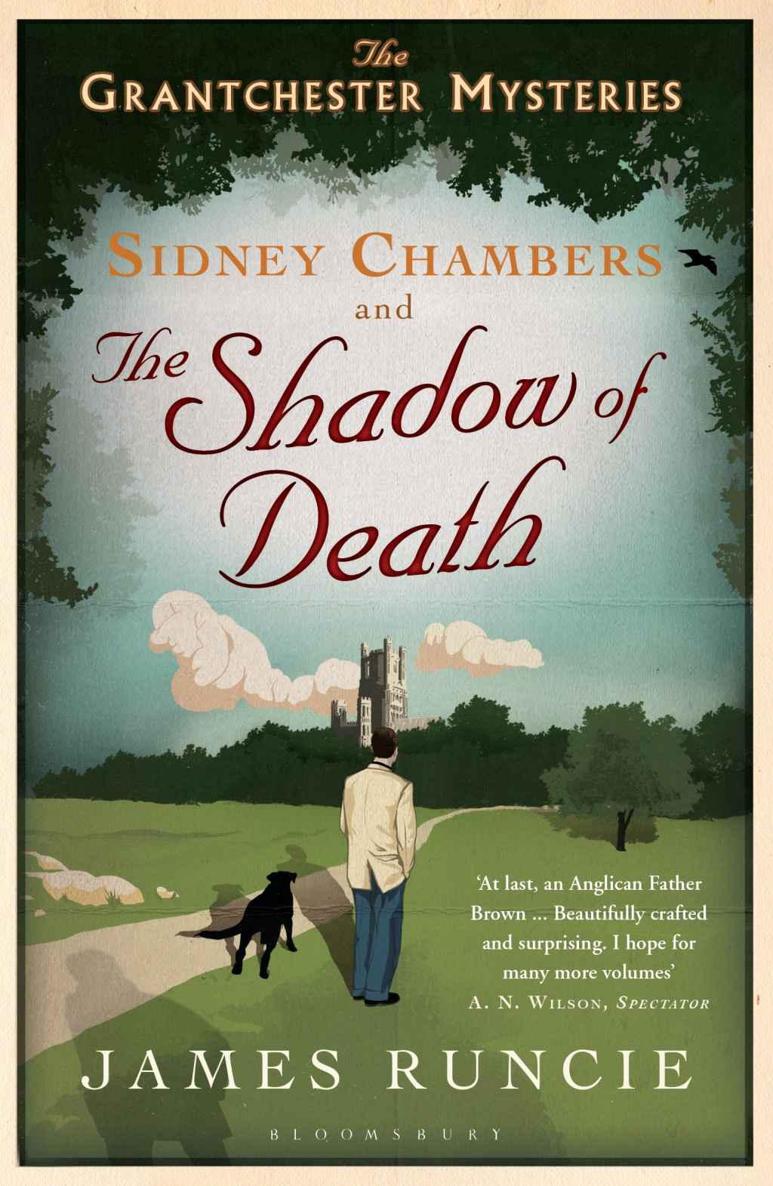

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

offered him tea.

His hostess was wearing the same green housecoat and appeared nervous; embarrassed even. ‘I am sorry I was in a dream when you last came. It was unfortunate. I could speak to people after the funeral because it was soon and I knew that I had to. Then afterwards . . . it was the shock, I think.’

‘I did not think that you were in a dream.’

‘I am sure I was rude. And sometimes, when I am sad, my English disappears. Do you speak any German?’

‘ Nur ein wenig . . . Können Sie mir den Weg zur nächsten Stadt zeigen ? ’

Hildegard laughed.

‘From the war, you understand. Sie sind eine sehr anziehende junge Dame. Spielen Sie Fußball ? ’

‘No, Canon Chambers I do not play football. Würden Sie gerne tanzen ? ’

‘ Ach, ich bin kein Tänzer. I am afraid I am not a dancer.’

‘ Was für eine Schande. Did you find out about the will?’ she asked.

‘I am afraid that there doesn’t seem to be one. But as his wife, you will no doubt be the beneficiary. This house, his savings . . .’

‘I am afraid there are more likely to be debts. No doubt Miss Morrison will tell me.’

‘I take it that you are not too fond of Miss Morrison.’

‘I didn’t see her enough to have an opinion. I think she thought that she was more responsible for my husband’s well-being than I was myself. I did not mind too much. I have never found jealousy helpful . . .’

‘Although she might have been jealous of you, of course?’ Sidney began.

‘I do not think it likely that she was in love with my husband if that is what you mean. But she did like to know everything that was going on.’

‘I can imagine,’ Sidney replied. ‘But I gather he had a separate diary. So she can’t have known everything . . .’

‘How do you know about that?’

‘She told me.’

‘There is nothing much in it. The police returned it to me with what they said were his “effects”. I didn’t understand what they meant.’

‘Have you put them somewhere safe?’

‘They are here,’ Hildegard replied. ‘Would you like me to show you?’

‘You don’t have to.’

Hildegard took up a box from the sideboard. ‘It seems very strange now. It is like something in a museum, the few possessions of a life: a wallet, a diary, cigarettes and a pencil with a rubber on the top. Sometimes I think my husband could still come back and the house would be as he had left it. I pretend that he has not died. One morning I poured two cups of tea before I realised that I only needed one.’

‘I’m sorry . . .’ said Sidney.

Hildegard stood up and opened the box. ‘The police also asked if I wanted to keep the gun. What would I want with a gun?’ She handed Sidney her husband’s diary.

‘What is this life,’ she asked, ‘but days that have passed? My husband wrote down the things he had to remember in pencil and then when each day was over he rubbed out what had happened.’

‘An unusual habit . . .’

‘When I saw him doing this for the first time he smiled and told me that another day was gone. He sounded relieved. He was rubbing out his life. Sometimes he would leave the house late at night and go for a walk. He could be away for hours. I never knew where he went. He could disappear, morning or night, and when I asked he told me that he just wanted to keep the black dog away. I think he preferred the night, when there was no one to trouble him. That’s why he slept in the day – another hour could be lost.’

‘He slept in the day?’

‘After lunch; a sleep for one hour exactly, even in office hours. He stayed on into the evenings to make up for it and was always last to leave and lock up. Often he was late for dinner, or distracted, and sometimes I didn’t know what I could do or say to help him. I asked him if perhaps it made life worse, to wake up twice in a day . . .’

Sidney opened the diary. It was small and leather-bound; the leaves were of lightweight paper and it came with a rubber-topped pencil in its spine. The pages were so fragile that some had been torn through excessive rubbing out. Inside the front cover, written in an italic hand was the owner’s name, S. Staunton. On one page he read the word ‘Anniversary’ and on the first of August ‘H’s birthday’. The only other markings were the traces of a pencilled division between morning and afternoon – A.M. and P.M. Perhaps, Sidney thought, they were the remnants of appointments either side of his afternoon nap.

‘And he

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher