![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

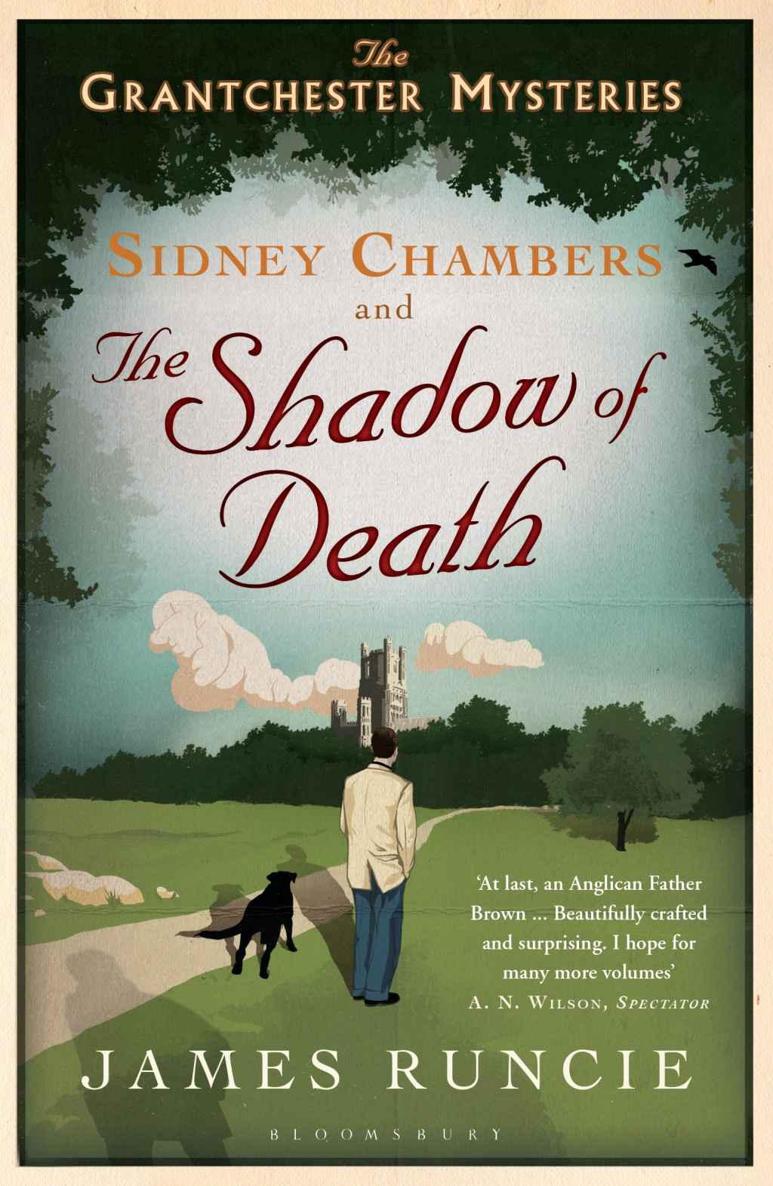

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

of my league.’

‘Perhaps, my dear Sidney, that is because you are in a league of your own. Happy birthday.’

She let her brother kiss her lightly and then looked out for her friend. The train doors were slamming. The train guard looked at his watch and put his whistle between his lips. Amanda returned. ‘We must hurry,’ she said, without appearing to do so. ‘Although I’ve told the guard to wait.’

She took Sidney’s hand in hers. ‘Happy birthday, Sidney. I do hope I can come again. Knowing you is such an adventure.’

‘You will always be welcome,’ Sidney smiled.

Amanda leant forward to kiss him. As she did so she accidentally brushed her lips against his. ‘I think you’re wonderful,’ she said, looking into his eyes.

‘Come on ,’ Jennifer called.

Sidney watched the two women board the London train and waved them goodbye. Then he bicycled back through the dark and icy roads to Grantchester. There were only a few, minor mishaps as he made his dreamy return; a front-wheel skid, a near miss with a cat and a wobble as he waved to a colleague from his college: the usual, unpredictable, moments that made it a relief to arrive home safely.

The next morning Sidney stooped down to pick up a letter that had arrived in the second post. It looked like a birthday card and it had been sent from Germany. The writing was Hildegard’s.

Sidney’s pleasure at receiving the letter was mixed with guilt about his friendship with Amanda. He passed it from one hand to the other, uncertain whether to open it or not. ‘I might just save this for later,’ he said to himself. ‘I think I’ve had enough excitement in my life for the time being.’

First, Do No Harm

One of the clerical undertakings that Sidney least enjoyed was the abstinence of Lent. The rejection of alcohol between Ash Wednesday and Easter Sunday had always been a tradition amongst the clergy of Cambridge but Sidney noticed that it neither improved their spirituality nor their patience. In fact, it made some of them positively murderous.

It had been a Siberian winter. The roads were blocked with drifted snow, rooks fell silent in the deep woods and arctic geese passed over fields where lambs had frozen to the ground. It was a bad time to be old, and Sidney had already spent too much time at the bedsides of elderly men and women who had fallen victim to influenza, hypothermia, pleurisy and pneumonia, a disease that seldom warranted its nickname as the old man’s friend. Instead, there was anxiety both in the village and in the town, a sense of unease and even unhappiness in the darkness. It was a world where people seldom looked up, but checked their footing on the road ahead, wary of falling, trusting neither weather nor fate.

What Sidney needed, he thought, was either a single malt or a pint of warm ale – perhaps even both – but he knew that he had to resist.

The strictures of this self-imposed restraint amused Inspector George Keating, who stuck to his regulation two pints of bitter on the regular backgammon night he shared with Sidney, each Thursday, in the RAF bar of The Eagle.

‘Still on the tonic water, Sidney? You don’t want me to liven it up with some gin? It’s cold out.’

‘I’m afraid not.’

‘Such a shame. Still, if you catch your death I can always slip you a brandy.’

‘That won’t be necessary. We are encouraged,’ Sidney continued dejectedly, as if he had learned the words by heart and no longer believed in them, ‘to reject such temptations and observe a time of fasting, prayer and silence.’

Inspector Keating tried to cheer things up. ‘You could have just the one. No one would notice. It is only us.’

‘But I would know. It would be on my conscience.’

‘I wish some of the members of the public had your self-awareness. This town would be a lot quieter if they did.’

‘The Anglican Church is supposed to be the conscience of the nation,’ Sidney mused. ‘We encourage people to believe that a moral life is, in fact, a happier life.’

‘People should be good for selfish reasons?’

‘Indeed. Shall we begin?’

Sidney laid out the backgammon on the old oak table in the lounge and the two men began to play their favourite game, gambling moderately for a penny a piece. Sidney found this to be one of the consoling moments of his week, a refuge from the cares of the world and the tribulations of office. He took a sip of his tonic water and tried to concentrate on the game. He threw

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher