![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

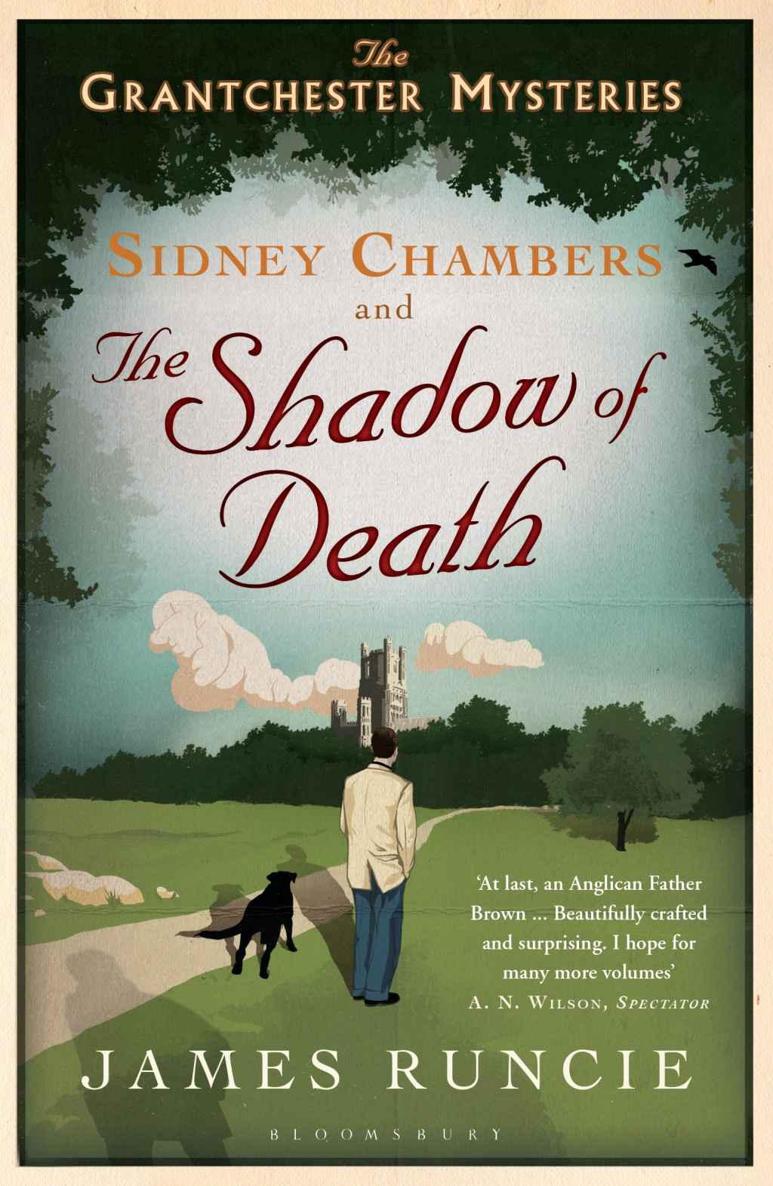

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

can’t stop thinking about her father,’ said Johnny. ‘I can’t imagine that was the first time. She must have stolen before.’

‘I’m not so sure,’ said Sidney.

Mark Dowland offered another explanation. ‘Perhaps she thought she deserved it more than Amanda. A better cause . . .’

‘I’ve always thought she was a bitch,’ said Guy.

‘Your thoughts on women are a disgrace,’ Amanda replied. It was the first time she had looked at him properly all evening. The ring was still in front of her. She looked at Sidney. ‘What shall I do with it now?’ she asked.

In 1954, Valentine’s Day, which was also Sidney’s birthday, fell on a Sunday. He was thirty-three years old. Because he was unable to leave his pastoral duties, his sister Jennifer brought Amanda up to Grantchester to mark the occasion. They came with cards from the rest of the family and a chocolate cake that they had made themselves. The celebration was to consist of a trip along the River Cam and a winter picnic.

It was a crisp but bright winter day and Jennifer and Amanda were sitting in the front of the punt with rugs over their knees and a hamper in front of them. It contained two flasks of milky tea laced with a little brandy; ham and mustard sandwiches; a selection of dainties from Fitzbillies; and the chocolate birthday cake with a candle which they would light at dusk.

Sidney was punting in his clerical cloak and he wore a wide-brimmed hat that made him look like a nineteenth-century eccentric. This was paradise, he thought: to be free of the cares of the world with his adorable sister and her beautiful best friend on his birthday. They would spend an hour or two chatting away and then the girls would return to London and Sidney would take Evensong and allow himself time to contemplate his blessings.

‘I have never known anything so unusual as a winter picnic on the river,’ said Amanda, ‘and I am enjoying it immensely. Where shall we moor?’

‘Just a little upstream,’ said Sidney. ‘Past Byron’s Pool. I know a spot.’

He dropped the pole into the water, pushed down, and then as he let the punt move away he began to recite: ‘Let us have wine and women, mirth and laughter, Sermons and soda-water the day after.’

‘Oh Byron,’ said Amanda. ‘My favourite poet. “Here’s a sigh to those who love me, And a smile to those who hate; And whatever sky’s above me, Here’s a heart for every fate.” ’

Sidney smiled. ‘I’m so glad that you seem to have recovered from all that sorry business on New Year’s Eve.’

‘Such a pity we couldn’t pin the whole business of the ring on Guy,’ Amanda replied. ‘I’d enjoy his fury at going to prison.’

‘That’s not very charitable.’

‘We’ve been generous enough with everyone else.’

‘You decided to let Daphne off?’ Sidney asked.

‘It would have finished her . . .’ Jennifer answered. ‘And Nigel was keen to avoid a scene.’

‘And so a crime has been ignored? That was very forgiving of you.’

‘We just have to trust she won’t ever do it again.’

Amanda was dubious. ‘I don’t see how we’ll ever know. I don’t think any of us will be inviting her again. But I suppose she did me a favour. Not that I’d tell her that.’

Sidney manoeuvred the punt round a corner, letting it glide past the frosted willows. ‘And you let Guy keep the ring?’

‘Oh yes,’ she replied. ‘He can give it to some other fool deluded by his so-called good looks. I don’t want it. It would just be a reminder of the whole ghastly evening. It was very good of your clerical friend to go all the way to Brighton and get it back. Are you taking him on?’

‘He should be joining me after Easter.’

‘Johnny thinks he might be a pansy,’ said Jennifer. ‘Do you?’

‘I wouldn’t dream of enquiring,’ Sidney replied as he ducked under a low branch of wych elm.

‘Isn’t that rather unlike you?’ Amanda inquired. ‘You have such an inquisitive mind.’

Sidney let the punt glide to the side of the river and moored in readiness for the picnic. ‘It is my belief that a private life should remain private. If Leonard Graham has something to tell me I am sure he will do so. I have asked him, in a rather informal way, to shave off his moustache. It makes him look a bit of a spiv and I don’t think it suits him. Other than that, I do not intend to pry.’

‘Even if your curiosity is piqued?’ his sister asked as she unwrapped the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher