![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

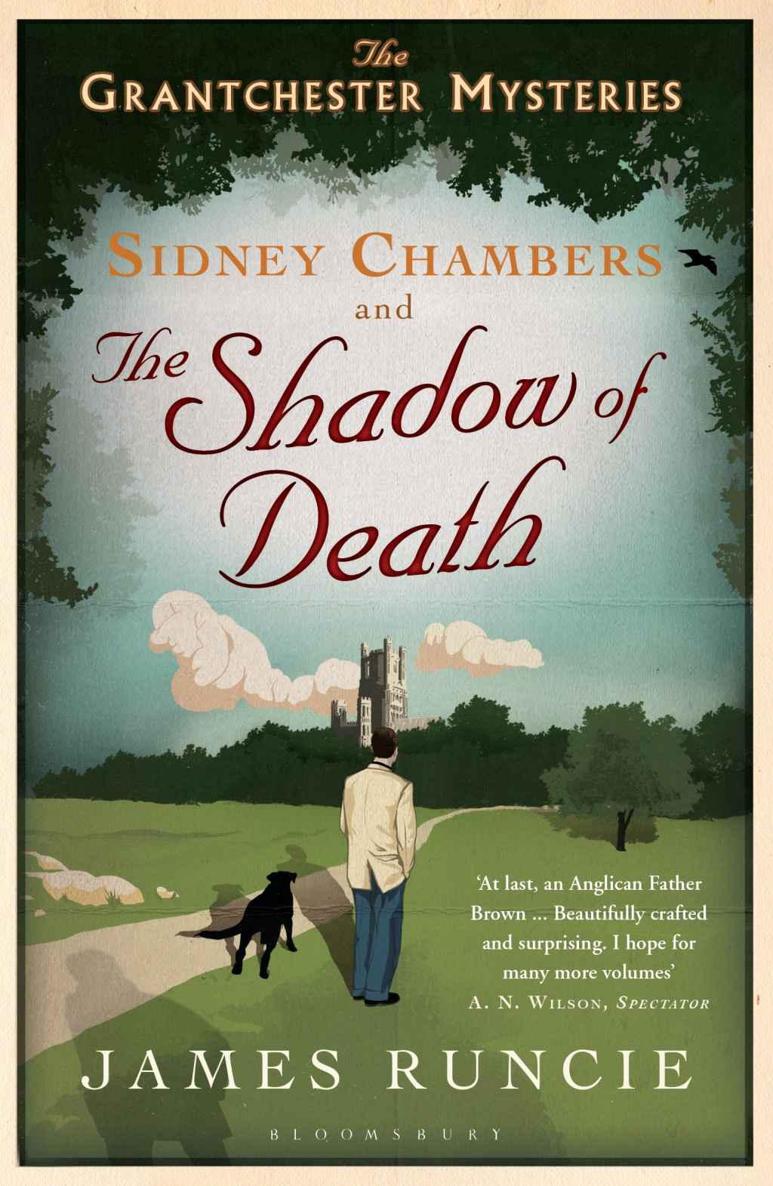

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

probably be rather a lot of it.’

At the beginning of March the snows began to melt and slide off the roofs, taking both shoppers and cyclists by surprise. Hawks hovered over the Meadows, and further out of town, in the fields around Grantchester, the farmers were able to plough and sow at last.

This was the hope of spring. Students unbuttoned their duffel coats and loosened their college scarves, children played football by the river and the first winter hyacinths began to appear in front windows.

Leonard Graham had settled in to one of the upper rooms of the vicarage. Sidney was happy to delegate duties, instruct him in the responsibilities of the ministry and let him preach sermons on the tensions between Kantian and Utilitarian ethics as often as he liked, providing he was kind to Mrs Maguire and was not impatient with those parishioners who had been spared a university education.

‘Natural wisdom,’ he told Leonard, ‘cannot always be found in books.’

‘I agree,’ his curate replied, ‘but to be naturally wise and then to read books gives you even more of an advantage.’

‘Over what?’ Sidney asked.

‘You think I am going to say “other people”, don’t you, Sidney, but that’s not what I mean at all. Reading gives you an advantage over life and time.’

‘I am aware of that,’ Sidney replied tersely.

‘You can travel through history, converse with the dead and live multiple lives . . .’

Sidney thought it sounded exhausting but his curate was unstoppable.

‘That is how I spend my free time,’ he continued. ‘I look to those who have lived before me in order to learn more about how to live now.’

‘I wish I had the opportunity to do that,’ Sidney replied. ‘But, alas, I do not.’

He knew that he was sounding pompous but he was distracted. He was waiting for the results of the coroner’s inquest. He still had not quite managed to pin down why Derek Jarvis unsettled him so much. He had thought that it was the black and white nature of his morality and the brisk efficiency with which he operated. But it might also be the fact that he was jealous. Sidney allowed his parishioners so much more time and so much more of a say when they were discussing their problems and their fears than the coroner ever did with his corpses. It was not that he resented this time, but sometimes he wished he could cut his meetings shorter and resolve the issues with which people came with more clarity. Perhaps, Sidney considered, he could even learn something from the coroner’s manner?

But no. Like a doctor, a priest had to allow events to run their course.

Sidney hesitated. Was this what Dr Michael Robinson had done? Had he allowed Dorothy Livingstone’s life to ‘run its course’ or had he hastened it towards its end? And if he had done so, were his intentions truly and only honourable and merciful? In short, were his actions those of a Christian?

As both a priest and an Englishman, Sidney liked to give people the benefit of the doubt, but he knew that he would have to find an excuse to see his doctor on his own and ask him a few direct questions.

He decided to make an appointment as a patient even though there was nothing specifically wrong with him. In fact, and in many ways, Sidney had never felt better in his life. He could perhaps go to the doctor’s surgery in Trumpington Road with talk of headaches, migraines even, but he did not want to suggest anything that might lead to an investigation or a hospital visit for tests.

‘Gout?’ he wondered idly. It had done for Milton, Cromwell and Henry VIII but did he really want to be associated with ‘the rheumatism of the rich’? Besides, his current abstinence would surely rule that out.

By the time Dr Robinson had asked, ‘What can I do for you?’ Sidney had still not thought of a convincing complaint.

‘I’d like you to take my blood pressure.’

‘Any reason?’

‘My heart seems to beat at different rates at different times of the day. I am more aware of it than I normally am.’

‘Roll up your sleeve. Any pain?’

‘No, I don’t think so. But sometimes I feel a bit fragile . . .’

‘That’s normal.’ Dr Robinson wrapped a cuff around Sidney’s upper left arm.

‘Is it?’

‘We can all feel a little delicate during difficult times, Canon Chambers.’

‘Yes, I suppose it must be very trying for you at the moment.’

Michael Robinson began to inflate the cuff until Sidney’s artery was occluded.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher