![Speaker for the Dead]()

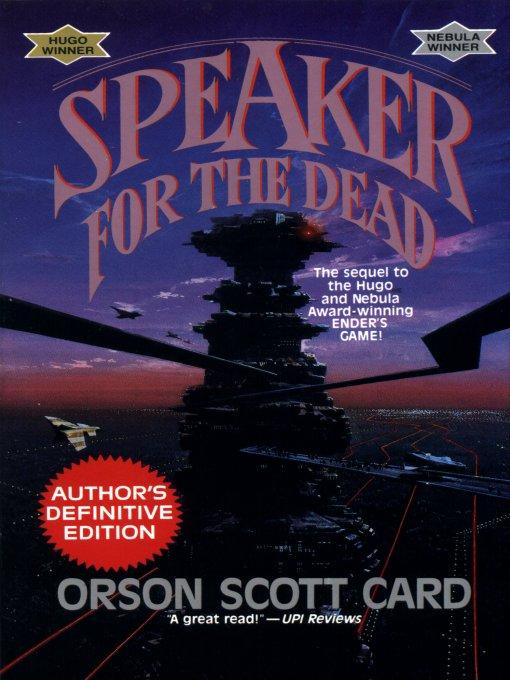

Speaker for the Dead

sullen and vicious crimes. But there were too many other lights on, including her own room and the front room. Something unusual was going on, and she didn't like unusual things.

Olhado sat in the living room, earphones on as usual; tonight, though, he also had the interface jack attached to his eye. Apparently, he was retrieving old visual memories from the computer, or perhaps dumping out some he had been carrying with him. As so many times before, she wished she could also dump out her visual memories and wipe them clean, replace them with more pleasant ones. Pipo's corpse, that would be one she'd gladly be rid of, to be replaced by some of the golden glorious days with the three of them together in the Zenador's Station. And Libo's body wrapped in its cloth, that sweet flesh held together only by the winding fabric; she would like to have instead other memories of his body, the touch of his lips, the expressiveness of his delicate hands. But the good memories fled, buried too deep under the pain. I stole them all, those good days, and so they were taken back and replaced by what I deserved.

Olhado turned to face her, the jack emerging obscenely from his eye. She could not control her shudder, her shame. I'm sorry, she said silently. If you had had another mother, you would doubtless still have your eye. You were born to be the best, the healthiest, the wholest of my children, Lauro, but of course nothing from my womb could be left intact for long.

She said nothing of this, of course, just as Olhado said nothing to her. She turned to go back to her room and find out why the light was on.

"Mother," said Olhado.

He had taken the earphones off, and was twisting the jack out of his eye.

"Yes?"

"We have a visitor," he said. "The Speaker."

She felt herself go cold inside. Not tonight, she screamed silently. But she also knew that she would not want to see him tomorrow, either, or the next day, or ever.

"His pants are clean now, and he's in your room changing back into them. I hope you don't mind."

Ela emerged from the kitchen. "You're home," she said. "I poured some cafezinhos, one for you, too."

"I'll wait outside until he's gone," said Novinha.

Ela and Olhado looked at each other. Novinha understood at once that they regarded her as a problem to be solved; that apparently they subscribed to whatever the Speaker wanted to do here. Well, I'm a dilemma that's not going to be solved by you.

"Mother," said Olhado, "he's not what the Bishop said. He's good."

Novinha answered him with her most withering sarcasm. "Since when are you an expert on good and evil?"

Again Ela and Olhado looked at each other. She knew what they were thinking. How can we explain to her? How can we persuade her? Well, dear children, you can't. I am unpersuadable, as Libo found out every week of his life. He never had the secret from me. It's not my fault he died.

But they had succeeded in turning her from her decision. Instead of leaving the house, she retreated into the kitchen, passing Ela in the doorway but not touching her. The tiny coffee cups were arranged in a neat circle on the table, the steaming pot in the center. She sat down and rested her forearms on the table. So the Speaker was here, and had come to her first. Where else would he go? It's my fault he's here, isn't it? He's one more person whose life I have destroyed, like my children's lives, like Marcão's, and Libo's, and Pipo's, and my own.

A strong yet surprisingly smooth masculine hand reached out over her shoulder, took up the pot, and began to pour through the tiny, delicate spout, the thin stream of hot coffee swirling into the tiny cafezinho cups.

"Posso derramar?" he asked. What a stupid question, since he was already pouring. But his voice was gentle, his Portuguese tinged with the graceful accents of Castilian. A Spaniard, then?

"Desculpa-me," she whispered. Forgive me. "Trouxe o senhor tantos quilômetros--"

"We don't measure starflight in kilometers, Dona Ivanova. We measure it in years." His words were an accusation, but his voice spoke of wistfulness, even forgiveness, even consolation. I could be seduced by that voice. That voice is a liar.

"If I could undo your voyage and return you twenty-two years, I'd do it. Calling for you was a mistake. I'm sorry." Her own voice sounded flat. Since her whole life was a lie, even this apology sounded rote.

"I don't feel the time yet," said the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher