![The Barker Street Regulars]()

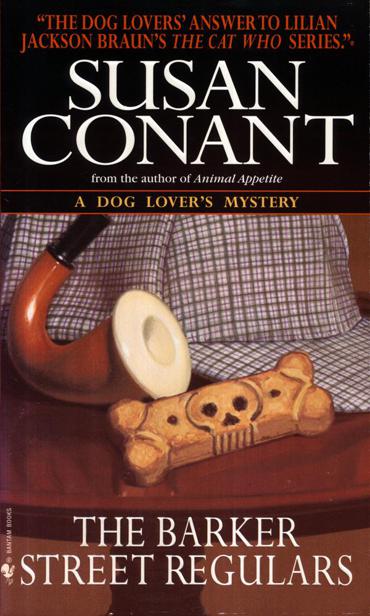

The Barker Street Regulars

camera, appeared on the terrace. Her fluttery manner hinted at the sort of dissociated woman who cloaks herself in full-length dead animals, but has hysterics at the sight of the furry corpses the cat drags home; I had the sense that practically from the moment she’d been born, everyone around her had engaged in a conspiratorial, if unconscious, program of operant conditioning that systematically reinforced that kind of internal split. If so, maybe Ceci’s dogs had made her whole again. She wasn’t wearing fur. Rather she had all but vanished inside a long, thick quilted coat, heavily padded boots, Polartec mittens, and a matching tam-o’-shanter. She was dressed to walk a dog on a cold night.

“Has my Simon been back?” She was childishly eager.

Robert, who seemed to specialize in dealing with Ceci, replied, “Someone or something has stood or been placed near this angle between the window and the wall of the house. The damage to the vegetation appears recent.”

“My Simon,” said Ceci indignantly, “would be most unlikely to tromp down my flowers.” With hurt feelings, she added, “And he’s never been this close to the house before.” As if mouthing someone else’s words, she said hopefully, “He is not yet ready. The time will come.”

“The hypothesis,” Robert said severely, “concerns the presence of a human being.”

Flinging a mittened hand toward the lower part of the yard, she said, “The police spent all their time below, where Jonathan had his accident.”

“Ceci,” Robert said firmly, “Holly is beginning to feel the cold. Take her in and give her a cup of hot tea.” Ceci agreed, but as I climbed the steps to the terrace and followed her through the open French door, she made the justifiable complaint that Hugh and Robert treated her like an imbecile. “I am perfectly competent. I went to Wellesley, you know, just like Madame Chiang Kai-shek, not that I stayed long, girls didn’t in those days, you know, I left to marry Ellis, girls did that back then, but Ellis made sure that I understood practical matters, he was a stockbroker, you know”—I hadn’t—“and I have always had my own checking account and reconciled my bank statements and taken care of my charge cards. You see, in his business,” she continued as I trailed after her into the kitchen, “he saw a great many women who suddenly lost their husbands and didn’t know how to make out a deposit slip or cash a check, never mind understanding investments, and he was determined not to leave me in that position. We’d no sooner returned from our honeymoon, Niagara Falls, less trite then than now, when Ellis sat me down and said, ’Ceci, buy and hold!’ ” Filling a teakettle, she concluded, “I am no imbecile!”

“Of course not,” I said. As I was reflecting that if I were in Ceci’s financial position, I’d forget Ellis’s dictum and sell enough to update the old-fashioned kitchen, Ceci hunted through a cupboard, extracted a box of graham crackers, and with an exasperated click of her tongue complained that Jonathan had polished off all the nice lemon wafers. Worse, Ceci said, instead of deplenishing the supply, Mary had gone and bought graham crackers. Ceci went on to lament Mary’s insistence on leaving at three in the afternoon. “And,” Ceci said, “she positively will not work weekends. But I must admit that she’s the first one I’ve had for longer than I care to remember who doesn’t smash the china, and when she is here, she’s a hard worker.”

Watching Ceci resentfully arrange a teapot, cups, saucers, spoons, a sugar bowl, a creamer, and a plate of the unsatisfactory graham crackers on a wooden tray, I sensed a gap between us that was as generational as it was financial: From Ceci’s viewpoint, why remodel a kitchen? Why spend money on the domain of the hired help?

If we were going to drink something, shouldn’t it be decaffeinated coffee? Brandy? Ovaltine? But tea was what Robert had suggested. I took Ceci’s compliance as a sign of suggestibility. We did not, of course, have our tea in the kitchen. Ceci politely rejected my offer to help with the tray. With no apparent effort, she lifted it herself and carried it across the kitchen and hall, and through the living room to a side table in the alcove. The potted palms, the bone china, the whole scene gave me the bizarre sense that I should be wearing white gloves and a perky little hat with a decorative veil. After sitting,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher