![The Girl You Left Behind]()

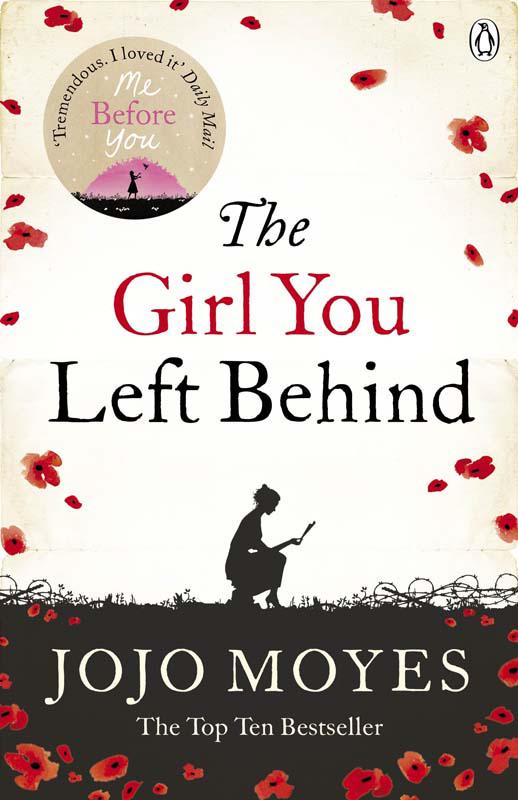

The Girl You Left Behind

Germans left in the evenings, Hélène and I would race to the fire,

extinguishing the logs then leaving them in the cellar to dry out. A few days’

collections of the half-burned oddments could mean a small fire in the daytime when it

was particularly cold. On the days we did that, the bar was often full to bursting, even

if few of our customers bought anything to drink.

But there was, predictably, a negative side.

Mesdames Durant and Louvier had decided that, even if I did nottalk

to the officers, or smile at them, or behave as if they were anything but a gross

imposition in my house, I must be receiving German largesse. I could feel their eyes on

me as I took in the regular supplies of food, wine and fuel. I knew we were the subject

of heated discussion around the square. My one consolation was that the nightly curfew

meant they could not see the glorious food we cooked for the men, or how the hotel

became a place of lively sound and debate during those dark evening hours.

Hélène and I had learned to live

with the sound of foreign accents in our home. We recognized a few of the men – there

was the tall thin one with the huge ears, who always attempted to thank us in our own

language. There was the grumpy one with the salt-and-pepper moustache, who usually

managed to find fault with something, demanding salt, pepper or extra meat. There was

little Holger, who drank too much and stared out of the window as if his mind was only

half on whatever was going on around him. Hélène and I would nod civilly at

their comments, taking care to be polite but not friendly. Some nights, if I’m

honest, there was almost a pleasure in having them there. Not Germans, but human beings.

Men, company, the smell of cooking. We had been starved of male contact, of life, for so

long. But there were other nights when evidently something had gone wrong, when they did

not talk, when faces were tight and severe, and the conversation was conducted in

rapid-fire bursts of whispering. They glanced sideways at us then, as if remembering

that we were the enemy. As if we could understand almost anything they said.

Aurélien was learning. He had taken to

lying on the floor of Room Three, his face pressed to the gap in the floorboards, hoping

that one day he might catch sight of a map or some instruction that would grant us

military advantage. He had become astonishingly proficient at German: when they were

gone he would mimic their accent or say things that made us laugh. Occasionally he even

understood snatches of conversation; which officer was in

der Krankenhaus

(hospital), how many men were

tot

. I worried for him, but I was proud too. It

made me feel that our feeding the Germans might have some hidden purpose yet.

The

Kommandant

, meanwhile, was

unfailingly polite. He greeted me, if not with warmth, then a kind of increasingly

familiar civility. He praised the food, without attempting to flatter, and kept a tight

hand on his men, who were not allowed to drink to excess or to behave in a forward

manner.

Several times he sought me out to discuss

art. I was not quite comfortable with one-to-one conversation, but there was a small

pleasure in being reminded of my husband. The

Kommandant

talked of his

admiration for Purrmann, of the artist’s German roots, of paintings he had seen by

Matisse that had made him long to travel to Moscow and Morocco.

At first I was reluctant to talk, and then I

found I could not stop. It was like being reminded of another life, another world. He

was fascinated by the dynamics of the Académie Matisse, whether there was rivalry

between the artists or genuine love. He had a lawyer’s way of speaking: quick,

intelligent, impatient towards those who could notimmediately grasp

his point. I think he liked to talk to me because I was not discomfited by him. It was

something in my character, I think, that I refused to appear cowed, even if I secretly

felt it. It had stood me in good stead in the haughty environs of the Parisian

department store, and it worked equally well for me now.

He had a particular liking for the portrait

of me in the bar, and would look at it for so long and discuss the technical merits of

Édouard’s use of colour, his brushstroke, that I was briefly able to forget

my awkwardness that I was its subject.

His own parents, he confided, were

‘not cultured’, but had inspired in him a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher