![The Lesson of Her Death]()

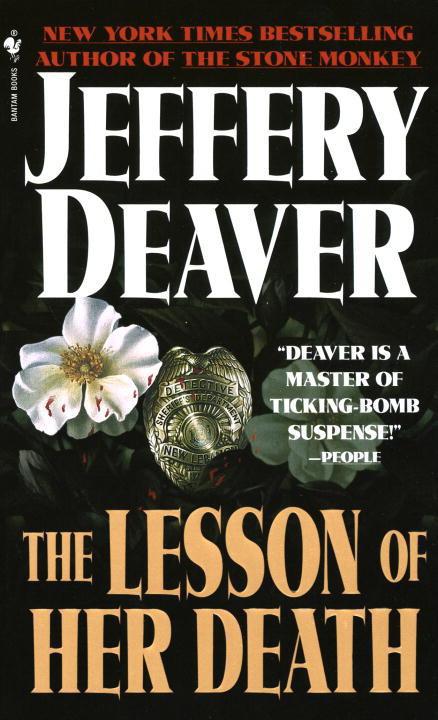

The Lesson of Her Death

given her a tranquilizer. She had a panic attack. They’re very dangerous in children.”

Although the doctor’s words were spoken softly Diane felt the lash of criticism again. She said in a spiny tone, “I was out and my husband had just got some bad news. We couldn’t deal with it all at once.”

“That’s what I’m here for.”

“I’m sorry,” Diane said. Then she was angry with herself.

Why should

I

feel guilty?

“I’ve kept her out of—”

“I know,” Dr. Parker said. “I called the school after you called me.”

“You did?” Diane asked.

“Of course I did. Sarah’s my patient. This incident is my responsibility.” The blunt admission surprised Diane but she sensed the doctor wasn’t apologizing; she was simply observing. “I misjudged her strength. She puts on a good facade of resilience. I thought she’d be better able to deal with the stress. I was wrong. I don’t want her back in school this term. We have to stabilize her emotionally.”

The doctor’s suit today was dark green and high-necked. Diane had noticed it favorably when she walked into the office and was even thinking of complimenting her. She changed her mind.

Dr. Parker opened a thick file. Inside were a half dozen booklets, on some of which Sarah’s stubby handwriting was evident. “Now I’ve finished my diagnosis and I’d like to talk to you about it. First, I was right to take her off Ritalin.”

I’m sure you’re always right

.

“She doesn’t display any general hyperkinetic activity and she’s very even-tempered when not confronted with stress. What I observed about her restlessness and her inattentiveness was that they’re symptomatic of her primary disability.”

“You said that might be the case,” Diane said.

“Yes, I did.”

But of course

.

“I’ve given her the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, the Gray Oral Reading Test, Bender Gestalt, Wide Range Achievement Test and the Informal Test of Written Language Expression. The results show your daughter suffers from severe reading retardation—”

“I don’t care what you say,” Diane blurted, “Sarah is not retarded.”

“That doesn’t mean that

she’s

retarded, Mrs. Corde. Primary reading retardation. It’s also called developmental dyslexia.”

“Dyslexia? That’s where you turn letters around.”

“That’s part of it. Dyslexics have trouble with word attack—that’s how we approach a word we’ve never seen before—and with putting together words or sentences. They have trouble with handwriting and show an intolerance for drill. Sarah also suffers from dysorthographia, or spelling deficit.”

Come on, Diplomas, cut out the big words and do what I’m paying you to do

.

“She has some of dyslexia’s mathematical counterpart—developmental dyscalculia. But her problem is primarily reading and spelling. Her combined verbal and performance IQ is in the superior range. In fact she’s functioning in the top five percent of the population. Her score, by the way, is higher than that of the average medical student.”

“Sarah?” Diane whispered.

“It’s also six points higher than your son’s. I checked with the school.”

Diane frowned. This could not be. The doctor’s credentials were suddenly suspect again.

“She’s reading about three years behind her chronological age and it usually happens that the gap will widen. Without special education, by the time she’s fifteen, Sarah’s writing age would be maybe eleven and her spelling age nine or

ten

.”

“What can we do?”

“Tutoring and special education. Immediately. Dyslexiais troubling with any student but it’s an extremely serious problem for someone with Sarah’s intelligence and creativity—”

“Creativity?” Diane could not suppress the laugh. Why, the doctor had mixed up her daughter’s file with another patient’s. “She’s not the

least

creative. She’s never painted anything. She can’t carry a tune. She can’t even strum a guitar. Obviously she can’t write …”

“Mrs. Corde, Sarah is one of the most creative patients I’ve ever had. She can probably do all of those things you just mentioned. She’s been too inhibited to try because the mechanics overwhelm her. She’s been conditioned to fail. Her self-esteem is very low.”

“But we always encourage her.”

“Mrs. Corde, parents often encourage their disabled children to do what other students can do easily. Sarah is not like other children.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher