![The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)]()

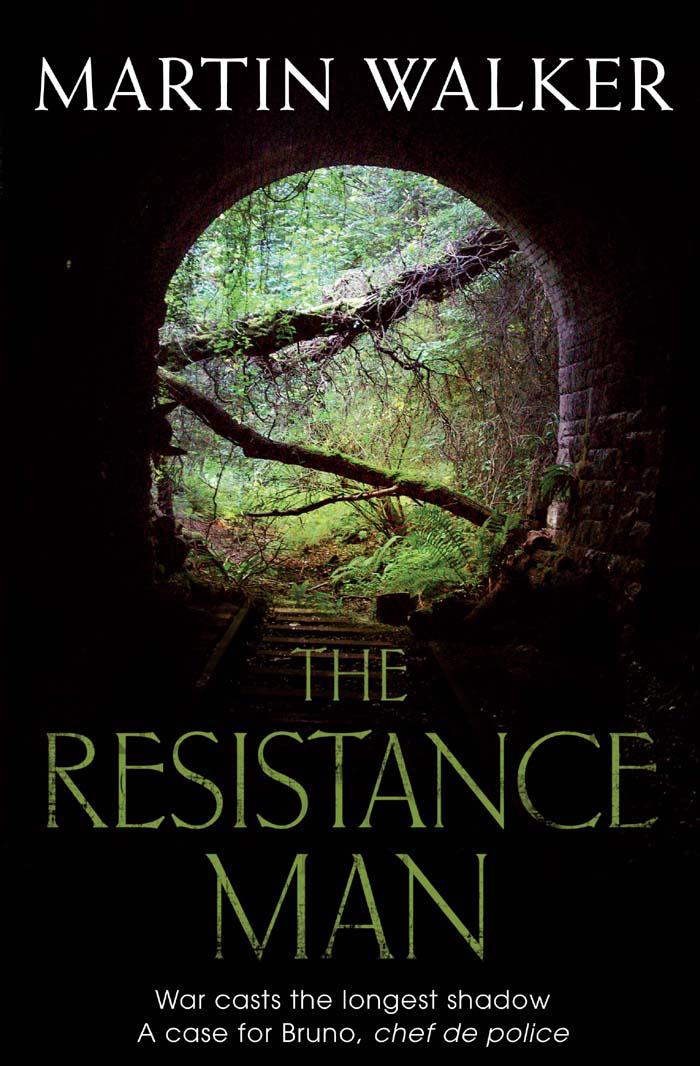

The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)

to put it all together.’

‘The Mayor seems to think it will have quite an impact, that you have found lots of new material,’ Bruno said.

‘We’ll see.’ She went into the adjoining kitchen. Bruno heard a clatter of cups and the whir of a coffee grinder. She poked her head round the door and continued talking. ‘He’s a good man, your Mayor. It’s such a shame about his wife. I’m giving him dinner tonight after he gets back from visiting her in hospital. Left to himself, he’d just have a sandwich, one of those men who are useless on their own.’

‘We’re hoping she’ll be able to come home soon.’

‘She’s not coming home,’ came the voice from the kitchen. ‘You don’t come back from galloping lymphatic cancer.’

Bruno was stunned. The Mayor had kept his wife’s condition a secret from everyone, at least everyone but Jacqueline.

‘You mean you didn’t know?’ she said, poking her head out again. ‘

Putain

, me and my big mouth. I’m really sorry, I thought his friends knew.’

Maybe some of them, thought Bruno. He’d thought he was pretty close to his Mayor, but evidently not. And he was sure nobody else at the

Mairie

knew. Obviously the Mayor’s relationship with Jacqueline was closer than he’d thought.

‘Let’s forget it, OK?’ she said, coming into the room. ‘And don’t tell him I told you. You were asking about the Neuvic train …’

She turned back into the kitchen and he heard a metal tray being placed on a counter. He’d never been close to the Mayor’s wife, who had rarely appeared at the

Mairie

, but the news came as a shock. Cécile had never joined her husband in campaigning and seemed content to be a traditional wife, tending her home and her garden, politely greeting people in the market. She had stayed behind when the Mayor had gone to Paris to work in politics, and only joined him there once, for his investiture into the Senate.

Jacqueline re-entered the room with a tray, speaking as if the subject had never changed. ‘Parts of my work led me into aspects of Resistance finance, which is why I got interested in the Neuvic train, the slush-fund to end all slush-funds.’

‘Is this the manuscript?’ he asked as he cleared some more space for the tray with its fine porcelain cups and saucers and a cafetière. He gestured to the typescript in front of him, post-it notes in different colours scattered through the pages.

‘No, mine is still in the computer, with copies sent elsewhere round the net in case my hard drive dies. That happened to me once and it was hell. What you have there are my father’s memoirs, typed up from his handwritten journals.’

‘He was a diplomat, is that right?’

‘Yes, he was in the American Embassy after the war and then on the Marshall Plan, the rebuilding of Europe’s economies. That was where I first read about your train, where he called it the slush-fund.’

‘The Mayor reckons it was worth about three hundred million in today’s money,’ he said.

She shrugged as she rested both hands on the plunger of the cafetière and began to press down. ‘At the time it was worth a lot more in relative terms, at least until the devaluations. In 1945, the official exchange rate was just over a hundred francs to the dollar. But by 1949 it was over three hundred to the dollar. The money aboard the Neuvic train was certainly a vast amount, worth about five per cent of total government spending in 1946. Put it this way, the national education budget that year was 470 million francs, and the Neuvic train held about five times that.’

Five times the education budget? The proportion staggered him, but Jacqueline had just begun. There were at least three official inquiries into the fate of the Neuvic money, she explained, adding that they had all pretty much whitewashed the whole affair, claiming the money went to finance the Resistance and their families and some was used to bribe prison guards. That was true up to a point, she conceded, but only for a fraction of the money, maybe half or a little more. Millions had been stolen.

‘How much do you know about French politics after the war?’ she asked.

‘De Gaulle came to power after the liberation of Paris in 1944 but resigned in 1946,’ he replied. ‘I’m not sure why.’

‘That’s simple. De Gaulle wanted a strong presidency rather than the unstable parliaments of the pre-war days. The parties, who’d been in a coalition of Communists, Socialists and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher