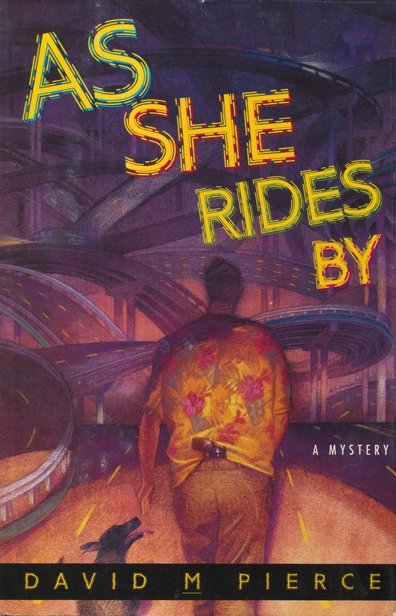

![Vic Daniel 6 - As she rides by]()

Vic Daniel 6 - As she rides by

me a limp handshake. “Of course, I haven’t been listening all that much lately, either.”

“You know,” I said, “you guys look vaguely familiar. Didn’t you used to be the Beatles or Gerry and the Pacemakers or Peter and Gordon or something?”

A deathly hush descended on the room. A frosty look descended over Jerry’s countenance. Tom made a retching noise in the back of his throat, then said, “Oh, sob, sob. Teardrops fall. My sight dims.”

“Gee,” I said. “Was it something I said?”

“Victor,” Rick said, coming to my rescue, “you are looking at the two originals, not some pale copy.”

“Oh.”

“You are looking at regulars on the Patti Page show, you are looking at millions of records sold.”

“Oh,”

“You are looking at triumphal tours, you are looking at every American high school girl’s wet dreams, here in the living flesh.”

“Well, mates,” I said, “it has suddenly occurred to me that I do know who you are after all and I remember you if not well, certainly with a sort of lingering affection. But the problem is, the two people who you happen to be are not called Tom and Jerry.”

“Ah, but we are to Rickie,” Jerry said.

“And to me,” the guy in the corner chipped in without turning around. I raised my eyebrows inquiring in his direction.

“L.R. Jones,” Rickie explained, giving a newly rolled joint a final, loving lick before lighting up. “I did a session a couple of days ago down at his place and during the break we were watching Miami Vice and I said my pal Vic would die laughing and he said why and so I told him and he said he’d like to meet you. Oodles of money. Collects early records. Fab pad. Made his fortune from Texas gushers following his wild and woolly youth, thus he is now known to one and all as Tex. Right, Jonesy?”

“I owe it all to the little woman,” Tex said. “She’s the brains in the family.”

“What’s he doing standing in the corner?” I whispered to Rick. “Did he bring something naughty to ‘Show and Tell’?”

“Nah,” Rick said loudly. “He thinks best in corners. At least he thinks he does.”

“Oh,” I said. “So OK, boys, what’s up?”

“Right,” said Jerry, all traces of pot-induced vagueness immediately vanishing. “Come on, chaps, let’s get some air.” He took his engineer’s cap off and ran a hand through his longish, wheat-colored tresses; with his thin mug and slightly high-bridged hooter he looked somewhat like a windblown Sherlock Holmes. Then he led the way toward the small kitchen. “We’ll be up top,” he said to Tex.

“Give me fifteen minutes,” Tex said. “I’ll join you.”

Tom and I followed Jerry to the kitchen. I snagged a Coke from the fridge and we went out the back door and up a semicircular flight of worn stone steps to a rickety-looking sun deck, where I lowered my frame cautiously into a deck chair and Tom and Jerry sat at opposite sides of a bleached-out picnic table, the kind with the two benches attached to the table itself. After a minute King came bounding up to join us.

It was a mild evening; there was still enough sun so that my half of the deck was getting some and the wooden floorboards were still pleasantly warm to the touch. Rickie’s fat, tortoiseshell cat was dozing in the shade on the house’s shingle roof just beside us; it opened one beady eye a slit, took in the three of us, then King, then closed it again.

“The music business,” Jerry said, “God bless it and all who sail in it. Know anything at all about it, old boy?”

“Too much and too little,” I said.

Jerry sighed. “OK,” I said, unzipping my windbreaker. “I know zilch about the business side. I don’t know how deals are made or what specific parties are involved. I’ve never seen a music contract or a recording contract or whatever it’s called, but I have a suspicion they are extremely lengthy.”

“Because the greater the length, the less chance of the poor old dumb musician understanding it,” Tom said.

“I know what a royalty is,” I said, “but I do not know how its percentage is determined, nor what that percentage is a percentage of.”

“I do,” Jerry said grimly. “Pity I didn’t fifteen years ago.”

“Also,” I said, “I know there is something called music publishing from which a recorded artist or writer derives income; I suppose it’s some kind of leftover from the days before records when a guy’s income would come mostly from the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher