![Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal]()

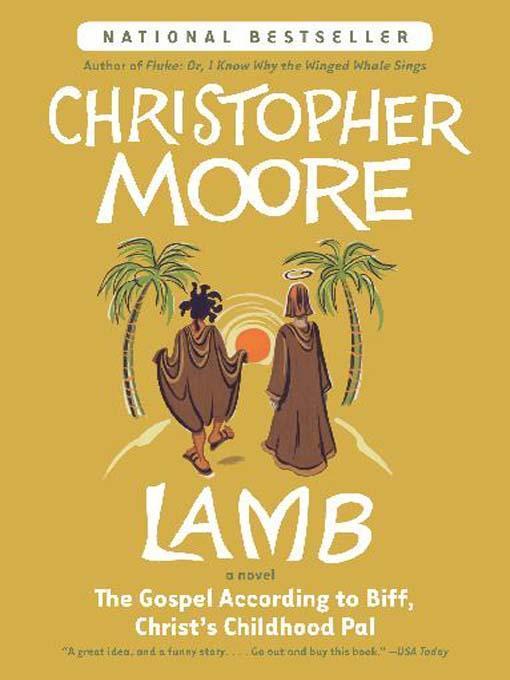

Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal

us loads of the white crystals that covered the floor of their home. There were six in the family, father, mother, an almost grown daughter, and three little ones. Another little son had been taken for sacrifice at the festival of Kali. Like Rumi, and all the other Untouchables, the Rajneesh family looked more like skeletons mummified in brown leather than people. The Untouchable men went about the pits naked or wearing only a loincloth, and even the women were dressed in tatters that barely covered them—nothing as nice as the stylish sari that I had purchased in the marketplace. Mr. Rajneesh commented that I was a very attractive woman and encouraged me to drop by after the next monsoon.

Joshua pounded chunks of the crystallized mineral into a fine white powder while Rumi and I collected charcoal from under the heated dying pit (a firebox had been gouged out of the stone under the pit) which the Untouchables used to render the flowers from the indigo shrub into fabric dye.

“I need brimstone, Rumi. Do you know what that is? A yellow stone that burns with a blue flame and gives off a smoke that smells like rotten eggs?”

“Oh yes, they sell it in the market as some sort of medicine.”

I handed the Untouchable a silver coin. Go buy as much of it as you can carry.”

“Oh my, this will be more than enough money. May I buy some salt with what is left?”

“Buy what you need with what’s left over, just go.”

Rumi skulked away and I went to help Joshua process the saltpeter.

The concept of abundance was an abstract one to the Untouchables, except as it pertained to two categories, suffering and animal parts. If you wanted decent food, shelter, or clean water, you would be sorely disappointed among the Untouchables, but if you were in the market for beaks, bones, teeth, hides, sinew, hooves, hair, gallstones, fins, feathers, ears, antlers, eyeballs, bladders, lips, nostrils, poop chutes, or any other inedible part of virtually any creature that walked on, swam under, or flew over the subcontinent of India, then the Untouchables were likely to have what you wanted lying around, conveniently stored beneath a thick blanket of black flies. In order to fashion the equipment I needed for my plan, I had to think in terms of animal parts. Fine unless you need, say, a dozen short swords, bows and arrows, and chain mail for thirty soldiers and all you have to work with is a stack of nostrils and three mismatched poop chutes. It was a challenge, but I made do. As Joshua moved among the Untouchables, surreptitiously healing their maladies, I barked out my orders.

“I need eight sheep bladders—fairly dry—two handfuls of crocodile teeth, two pieces of rawhide as long as my arms and half again as wide. No, I don’t care what kind of animal, just not too ripe, if you can manage it. I need hair from an elephant’s tail. I need firewood, or dried dung if you must, eight oxtails, a basket of wool, and a bucket of rendered fat.”

And a hundred scrawny Untouchables stood there, eyes as big as saucers, just staring at me while Joshua moved among them, healing their wounds, sicknesses, and insanities, without any of them suspecting what was happening. (We’d agreed that this was the wisest tack to take, as we didn’t want a bunch of healthy Untouchables athletically bounding through Kalighat proclaiming that they had been cured of all ills by a strange foreigner, thus attracting attention to us and spoiling my plan. On the other hand, neither could we stand there and watch these people suffer, knowing that we—well, Joshua—had the power to help them.) He’d also taken to poking one of them in the arm with his finger anytime anyone said the word “Untouchable.” Later he told me that he just hated passing up the opportunity for palpable irony. I cringed when I saw Joshua touching the lepers among them, as if after all these years away from Israel a tiny Pharisee stood on my shoulder and screamed, “Unclean!”

“Well?” I said after I’d finished my orders. “Do you want your children back or not?”

“We don’t have a bucket,” said one woman.

“Or a basket,” said another.

“Okay, fill some of the sheep bladders with rendered fat, and bundle the wool in some kind of hide. Now go, we don’t have a lot of time.”

And they all stood and looked at me. Big eyes. Sores healed. Parasites purged. They just looked at me. “Look, I know my Sanskrit isn’t great, but you do know what I am

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher