![Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal]()

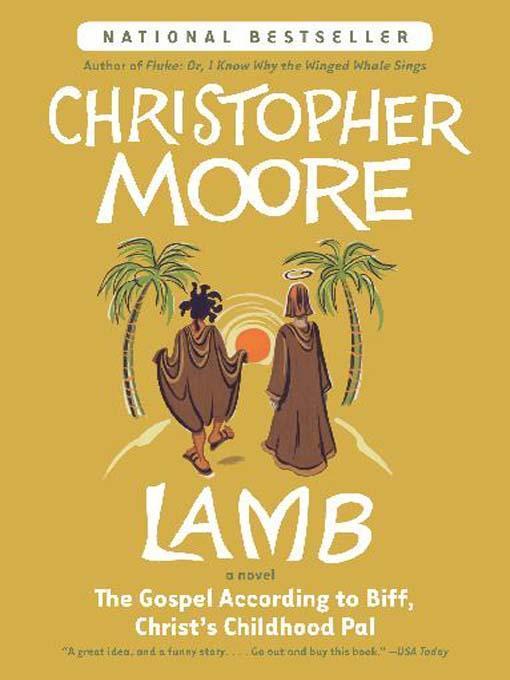

Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal

journey was two months by camel, what will that mean to these people who can cross an ocean in hours? I need to know modern distances.”

“No,” said the angel.

(Did you know that in a hotel they bolt the bedside lamp to the table, thereby making it an ineffective instrument of persuasion when trying to bring an obdurate angel around to your way of thinking? Thought you should know that. Pity too, it’s such a substantial lamp.)

“But how will I recount the heroic acts of the archangel Raziel if I can’t tell the locations of his deeds? What, you want me to write, ‘Oh, then somewhere generally to the left of the Great Wall that rat-bastard Raziel showed up looking like hell considering he may have traveled a long distance or not?’ Is that what you want? Or should it read, ‘Then, only a mile out of the port of Ptolemais, we were once again graced with the shining magnificence of the archangel Raziel? Huh, which way do you want it?”

(I know what you’re thinking, that the angel saved my life when Titus threw me off the ship and that I should be more forgiving toward him, right? That I shouldn’t try to manipulate a poor creature who was given an ego but no free will or capacity for creative thought, right? Okay, good point. But do please remember that the angel only intervened on my behalf because Joshua was praying for my rescue. And do please remember that he could have saved us a lot of difficulty over the years if he had helped us out more often. And please don’t forget that—despite the fact that he is perhaps the most handsome creature I’ve ever laid eyes on—Raziel is a stone doofus. Nevertheless, the ego stroke worked.)

“I’ll get you a map.”

And he did. Unfortunately the concierge was only able to find a map of the world provided by an airline that partners with the hotel. So who knows how accurate it is. On this map the next leg of our journey is six inches long and would cost thirty thousand Friendly Flyer Miles. I hope that clears things up.

The trader’s name was Ahmad Mahadd Ubaidullaganji, but he said we could call him Master. We called him Ahmad. He led us through the city to a hillside where his caravan was camped. He owned a hundred camels which he drove along the Silk Road, along with a dozen men, two goats, three horses, and an astonishingly homely woman named Kanuni. He took us to his tent, which was larger than both the houses Joshua and I had grown up in. We sat on rich carpets and Kanuni served us stuffed dates and wine from a pitcher shaped like a dragon.

“So, what does the Son of God want with my friend Balthasar?” Ahmad asked. Before we could answer he snorted and laughed until his shoulders shook and he almost spilled his wine. He had a round face with high cheekbones and narrow black eyes that crinkled at the corners from too much laughter and desert wind. “I’m sorry, my friends, but I’ve never been in the presence of the son of a god before. Which god is your father, by the way?”

“Well, the God,” I said.

“Yep,” said Joshua. “That’s the one.”

“And what is your God’s name?”

“Dad,” said Josh.

“We’re not supposed to say his name.”

“Dad!” said Ahmad. “I love it.” He started giggling again. “I knew you were Hebrews and weren’t allowed to say your God’s name, I just wanted to see if you would. Dad. That’s rich.”

“I don’t mean to be rude,” I said, “and we are certainly enjoying the refreshments, but it’s getting late and you said you would take us to see Balthasar.”

“And indeed I will. We leave in the morning.”

“Leave for where?” Josh asked.

“Kabul, the city where Balthasar lives now.”

I had never heard of Kabul, and I sensed that was not a good thing. “And how far is Kabul?”

“We should be there in less than two months by camel,” Ahmad said.

If I knew then what I know now, I might have stood and exclaimed, “Tarnation, man, that’s over six inches and thirty thousand Friendly Flyer Miles!” But since I didn’t know that then, what I said was “Shit.”

“I will take you to Kabul,” said Ahmad, “but what can you do to help pay your way?”

“I know carpentry,” Joshua said. “My stepfather taught me how to fix a camel saddle.”

“And you?” He looked at me. “What can you do?”

I thought about my experience as a stonecutter, and immediately rejected it. And my training as a village idiot, which I thought I could always fall back on, wasn’t

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher