![Pnin]()

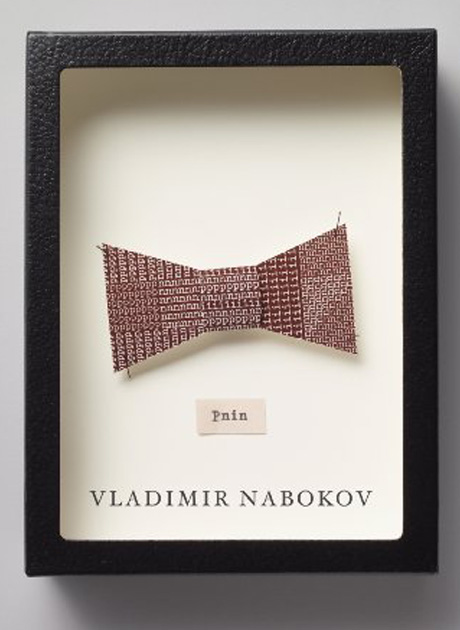

Pnin

exists here.'

'Impossible isolation,' said Pnin.

'Yes, but - Really, you are not playing fair, Timofey. You know perfectly well you agree with Lore that the world of the mind is based on a compromise with logic.'

'I have reservations,' said Pnin. 'First of all, logic herself -'

'All right, I'm afraid we are wandering away from our little joke. Now, you look at the picture. So this is the mariner, and this is the pussy, and this is a rather wistful mermaid hanging around, and now look at the puffs right above the sailor and the pussy.'

'Atomic bomb explosion,' said Pnin sadly.

'No, not at all. It is something much funnier. You see, these round puffs are supposed to be the projections of their thoughts. And now at last we are getting to the amusing part. The sailor imagines the mermaid as having a pair of legs, and the cat imagines her as all fish.'

'Lermontov,' said Pnin, lifting two fingers, 'has expressed everything about mermaids in only two poems. I cannot understand American humour even, when I am happy, and I must say -' He removed his glasses with trembling hands, elbowed the magazine aside, and, resting his head on his arm, broke into muffled sobs.

She heard the front door open and close, and a moment later Laurence peeped into the kitchen with facetious furtiveness. Joan's right hand waved him away; her left directed him to the rainbow-rimmed envelope on top of the parcels. The private smile she flashed was a summary of Isabel's letter; he grabbed it and, no more in jest, tiptoed out again.

Pnin's unnecessarily robust shoulders continued to shake. She closed the magazine and for a minute studied its cover: toy-bright school tots, Isabel and the Hagen child, shade trees still off duty, a white spire, the Waindell bells.

'Doesn't she want to come back?' asked Joan softly.

Pnin, his head on his arm, started to beat the table with his loosely clenched fist.

'I haf nofing,' wailed Pnin between loud, damp sniffs, 'I haf nofing left, nofing, nofing!'

Chapter Three

1

During the eight years Pnin had taught at Waindell College he had changed his lodgings - for one reason or another, mainly sonic - about every semester. The accumulation of consecutive rooms in his memory now resembled those displays of grouped elbow chairs on show, and beds, and lamps, and inglenooks which, ignoring all space-time distinctions, commingle in the soft light of a furniture store beyond which it snows, and the dusk deepens, and nobody really loves anybody. The rooms of his Waindell period looked especially trim in comparison with one he had had in uptown New York, midway between Tsentral Park and Reeverside, on a block memorable for the waste-paper along the curb, the bright pat of dog dirt somebody had already slipped upon, and a tireless boy pitching a ball against the steps of the high brown porch; and even that room became positively dapper in Pnin's mind (where a small ball still rebounded) when compared with the old, now dust-blurred lodgings of his long Central-European, Nansen-passport period.

With age, however, Pnin had become choosy. Pretty fixtures no longer sufficed. Waindell was a quiet townlet, and Waindellville, in a notch of the hills, was yet quieter; but nothing was quiet enough for Pnin. There had been, at the start of his life here, that studio in the thoughtfully furnished College Home for Single Instructors, a very nice place despite certain gregarious drawbacks ('Ping-pong, Pnin?' 'I don't any more play at games of infants'), until workmen came and started to drill holes in the street - Brainpan Street, Pningrad - and patch them up again, and this went on and on, in fits of shivering black zigzags and stunned pauses, for weeks, and it did not seem likely they would ever find again the precious tool they had entombed by mistake. There had been (to pick out here and there only special offenders) that room in the eminently hermetic-looking Duke's Lodge, Waindellville: a delightful kabinet, above which, however, every evening, among crashing bathroom cascades and banging doors, two monstrous statues on primitive legs of stone would grimly tramp - shapes hard to reconcile with the slender build of his actual upstairs neighbours, who turned out to be the Starrs, of the Fine Arts Department ('I am Christopher, and this is Louise'), an angelically gentle couple keenly interested in Dostoyevsky and Shostakovich. There had been - in yet another rooming house - a still cosier bedroom-study, with nobody butting in

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher