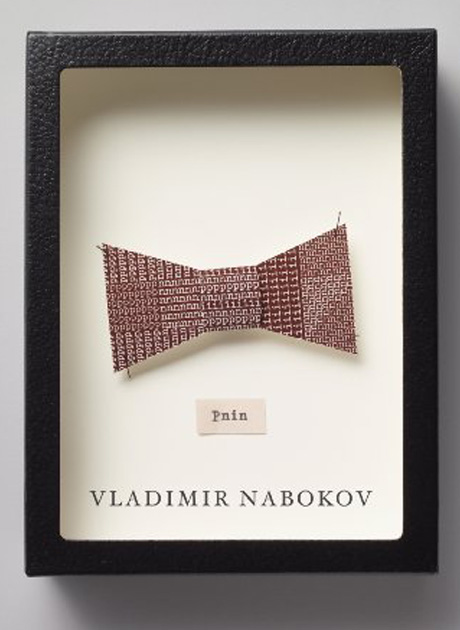

![Pnin]()

Pnin

away what she wanted of him the day might slow down and be really enjoyed.

'What a gruesome place, kakoy zhutkiy dom,' she said, sitting on the chair near the telephone and taking off her galoshes - such familiar movements! 'Look at that aquarelle with the minarets. They must be terrible people.'

'No,' said Pnin, 'they are my friends.'

'My dear Timofey,' she said, as he escorted her upstairs, 'you have had some pretty awful friends in your time.'

'And here is my room,' said Pnin.

'I think I'll lie on your virgin bed, Timofey. And I'll recite you some verses in a minute. That hellish headache of mine is seeping back again. I felt so splendid all day.'

'I have some aspirin.'

'Uhn-uhn,' she said, and this acquired negative stood out strangely against her native speech.

He turned away as she started to take off her shoes, and the sound they made toppling to the floor reminded him of very old days.

She lay back, black-skirted, white-bloused, brown-haired, with one pink hand over her eyes.

'How is everything with you?' asked Pnin (have her say what she wants of me, quick!) as he sank into the white rocker near the radiator.

'Our work is very interesting,' she said, still shielding her eyes, 'but I must tell you I don't love Eric any more. Our relations have disintegrated. Incidentally, Eric dislikes his child. He says he is the land father and you, Timofey, are the water father.'

Pnin started to laugh: he rolled with laughter, the rather juvenile rocker fairly cracking under him. His eyes were like stars and quite wet.

She looked at him curiously for an instant from under her plump hand - and went on:

'Eric is one hard emotional block in his attitude toward Victor. I don't know how many times the boy must have killed him in his dreams. And, with Eric, verbalization - I have long noticed - confuses problems instead of clarifying them. He is a very difficult person. What is your salary, Timofey?'

He told her.

'Well,' she said, 'it is not grand. But I suppose you can even lay something aside - it is more than enough for your needs, for your microscopic needs, Timofey.'

Her abdomen tightly girdled under the black skirt jumped up two or three times with mute, cosy, good-natured reminiscential irony - and Pnin blew his nose, shaking his head the while, in voluptuous, rapturous mirth.

'Listen to my latest poem,' she said, her hands now along her sides as she lay perfectly straight on her back, and she sang out rhythmically, in long-drawn, deep-voiced tones:

'Ya nadela tyomnoe plat'e,

I monashenki ya skromney;

Iz slonovoy kosti raspyat'e

Nad holodnoy postel'yu moey.

No ogni nebïvalïh orgiy

Prozhigayut moyo zabïtyo

I shepchu ya imya Georgiy -

Zolotoe imya tvoyo!

(I have put on a dark dress

And am more modest than a nun;

An ivory crucifix

Is over my cold bed.

But the lights of fabulous orgies

Burn through my oblivion,

And I whisper the name George -

Your golden name!)'

'He is a very interesting man,' she went on, without any interval. 'Practically English, in fact. He flew a bomber in the war and now he is with a firm of brokers who have no sympathy with him and do not understand him. He comes from an ancient family. His father was a dreamer, had a floating casino, you know, and all that, but was ruined by some Jewish gangsters in Florida and voluntarily went to prison for another man; it is a family of heroes.'

She paused. The silence in the little room was punctuated rather than broken by the throbbing and tinkling in those whitewashed organ pipes.

'I made Eric a complete report,' Liza continued with a sigh. 'And now he keeps assuring me he can cure me if I cooperate. Unfortunately, I am also cooperating with George.'

She pronounced George as in Russian - both g's hard, both e's longish.

'Well, c'est la vie, as Eric so originally says. How can you sleep with that string of cobweb hanging from the ceiling?' She looked at her wrist-watch. 'Goodness, I must catch the bus at four-thirty. You must call a taxi in a minute. I have something to say to you of the utmost importance.'

Here it was coming at last - so late.

She wanted Timofey to lay aside every month a little money for the boy - because she could not ask Bernard Maywood now - and she might die - and Eric did not care what happened - and somebody ought to send the lad a small sum now and then, as if coming from his mother - pocket money, you know - he would be among rich boys. She would write Timofey giving him an address and some

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher