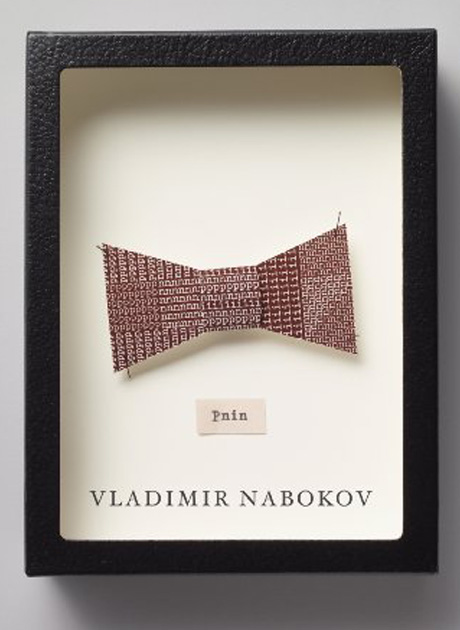

![Pnin]()

Pnin

Finally, as they walked along a meadow path, brushing against the golden rod, toward the wood where a rocky river ran, they spoke of their healths: Chateau, who looked so jaunty, with one hand in the pocket of his white flannel trousers and his lustring coat rather rakishly opened on a flannel waistcoat, cheerfully said that in the near future he would have to undergo an exploratory operation of the abdomen, and Pnin said, laughing, that every time he was X-rayed, doctors vainly tried to puzzle out what they termed' a shadow behind the heart'.

'Good title for a bad novel,' remarked Chateau.

As they were passing a grassy knoll just before entering the wood, a pink-faced venerable man in a seersucker suit, with a shock of white hair and a tumefied purple nose resembling a huge raspberry, came striding toward them down the sloping field, a look of disgust contorting his features.

'I have to go back for my hat,' he cried dramatically as he drew near.

'Are you acquainted?' murmured Chateau, fluttering his hands introductively 'Timofey Pavlich Pnin, Ivan Ilyich Gramineev.'

'Moyo pochtenie (My respects),' said both men, bowing to each other over a powerful handshake.

'I thought,' resumed Gramineev, a circumstantial narrator, 'that the day would continue as overcast as it had begun. By stupidity (po gluposti) I came out with an unprotected head. Now the sun is' roasting my brains. I have to interrupt my work.'

He gestured toward the top of the knoll. There his easel stood in delicate silhouette against the blue sky. From that crest he had been painting a view of the valley beyond, complete with quaint old barn, gnarled apple tree, and kine.

'I can offer you my panama,' said kind Chateau, but Pnin had already produced from his bathrobe pocket a large red handkerchief: he expertly twisted each of its corners into a knot.

'Admirable.... Most grateful,' said Gramineev, adjusting this headgear.

'One moment,' said Pnin. 'You must tuck in the knots.'

This done, Gramineev started walking up the field toward his easel. He was a well-known, frankly academic painter, whose soulful oils - 'Mother Volga', 'Three Old Friends' (lad, nag, dog), 'April Glade', and so forth-still graced a museum in Moscow.

'Somebody told me,' said Chateau, as he and Pnin continued to progress riverward, 'that Liza's boy has an extraordinary talent for painting. Is that correct?'

'Yes,' answered Pnin. 'All the more vexing (tem bolee obidno) that his mother, who I think is about to marry a third time, took Victor suddenly to California for the rest of the summer, whereas if he had accompanied me here, as had been planned, he would have had the splendid opportunity of being coached by Gramineev.'

'You exaggerate the splendour,' softly rejoined Chateau.

They reached the bubbling and glistening stream. A concave ledge between higher and lower diminutive cascades formed a natural swimming pool under the alders and pines. Chateau, a non-bather, made himself comfortable on a boulder. Throughout the academic year Pnin had regularly exposed his body to the radiation of a sun lamp; hence when he stripped down to his bathing trunks, he glowed in the dappled sunlight of the riverside grove with a rich mahogany tint. He removed his cross and his rubbers.

'Look, how pretty,' said observant Chateau.

A score of small butterflies, all of one kind, were settled on a damp patch of sand, their wings erect and closed, showing their pale undersides with dark dots and tiny orange-rimmed peacock spots along the hindwing margins; one of Pnin's shed rubbers disturbed some of them and, revealing the celestial hue of their upper surface, they fluttered around like blue snow-flakes before settling again.

'Pity Vladimir Vladimirovich is not here,' remarked Chateau. 'He would have told us all about these enchanting insects.'

'I have always had the impression that his entomology was merely a pose.'

'Oh no,' said Chateau. 'You will lose it some day,' he added, pointing to the Greek Catholic cross on a golden chainlet that Pnin had removed from his neck and hung on a twig. Its glint perplexed a cruising dragonfly.

'Perhaps I would not mind losing it,' said Pnin. 'As you well know, I wear it merely from sentimental reasons. And the sentiment is becoming burdensome. After all, there is too much of the physical about this attempt to keep a particle of one's childhood in contact with one's breast bone.'

'You are not the first to reduce faith to a sense of touch,' said

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher