![Pnin]()

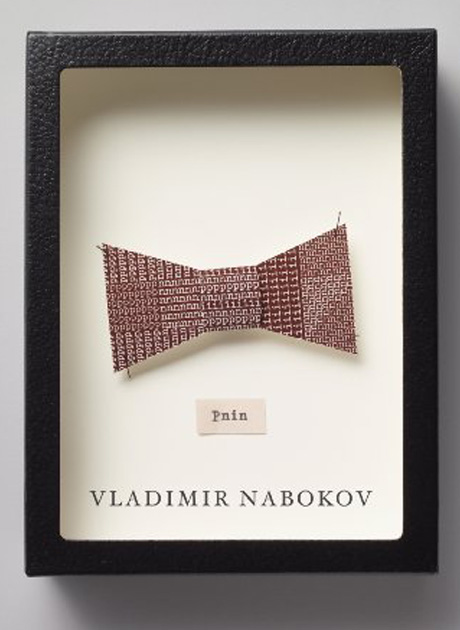

Pnin

don't get up) and sat down next to him on the bench.

'In 1916 or 1917,' she said, 'you may have had occasion to hear my maiden name - Geller - from some great friends of yours.'

'No, I don't recollect,' said Pnin.

'It is of no importance, anyway. I don't think we ever met. But you knew well my cousins, Grisha and Mira Belochkin. They constantly spoke of you. He is living in Sweden, I think - and, of course, you have heard of his poor sister's terrible end....'

'Indeed, I have,' said Pnin.

'Her husband,' said Madam Shpolyanski, 'was a most charming man, Samuil Lvovich and I knew him and his first wife, Svetlana Chertok, the pianist, very intimately. He was interned by the Nazis separately from Mira, and died in the same concentration camp as did my elder brother Misha. You did not know Misha, did you? He was also in love with Mira once upon a time.'

'Tshay gotoff (tea's ready),' called Susan from the porch in her funny functional Russian. 'Timofey, Rozochka! Tshay!'

Pnin told Madam Shpolyanski he would follow her in a minute, and after she had gone he continued to sit in the first dusk of the arbour, his hands clasped on the croquet mallet he still held.

Two kerosene lamps cosily illuminated the porch of the country house. Dr Pavel Antonovich Pnin, Timofey's father, an eye specialist, and Dr Yakov Grigorievich Belochkin, Mira's father, a paediatrician, could not be torn away from their chess game in a corner of the veranda, so Madam Belochkin had the maid serve them there - on a special small Japanese table, near the one they were playing at - their glasses of tea in silver holders, the curd and whey with black bread, the Garden Strawberries, zemlyanika, and the other cultivated species, klubnika (Hautbois or Green Strawberries), and the radiant golden jams, and the various biscuits, wafers, pretzels, zwiebacks - instead of calling the two engrossed doctors to the main table at the other end of the porch, where sat the rest of the family and guests, some clear, some grading into a luminous mist.

Dr Belochkin's blind hand took a pretzel; Dr Pnin's seeing hand took a rook. Dr Belochkin munched and stared at the hole in his ranks; Dr Pnin dipped an abstract zwieback into the hole of his tea.

The country house that the Belochkins rented that summer was in the same Baltic resort near which the widow of General N- let a summer cottage to the Pnins on the confines of her vast estate, marshy and rugged, with dark woods hemming in a desolate manor. Timofey Pnin was again the clumsy, shy, obstinate, eighteen-year-old boy, waiting in the dark for Mira - and despite the fact that logical thought put electric bulbs into the kerosene lamps and reshuffled the people, turning them into ageing émigrés and securely, hopelessly, forever wire-netting the lighted porch, my poor Pnin, with hallucinatory sharpness, imagined Mira slipping out of there into the garden and coming toward him among tall tobacco flowers whose dull white mingled in the dark with that of her frock. This feeling coincided somehow with the sense of diffusion and dilation within his chest. Gently he laid his mallet aside and, to dissipate the anguish, started walking away from the house, through the silent pine grove. From a car which was parked near the garden tool house and which contained presumably at least two of his fellow guests' children, there issued a steady trickle of radio music.

'Jazz, jazz, they always must have their jazz, those youngsters,' muttered Pnin to himself, and turned into the path that led to the forest and river. He remembered the fads of his and Mira's youth, the amateur theatricals, the gipsy ballads, the passion she had for photography. Where were they now, those artistic snapshots she used to take - pets, clouds, flowers, an April glade with shadows of birches on wet-sugar snow, soldiers posturing on the roof of a box-car, a sunset skyline, a hand holding a book? He remembered the last day they had met, on the Neva embankment in Petrograd, and the tears, and the stars, and the warm rose-red silk lining of her karakul muff. The Civil War of 1918-22 separated them: history broke their engagement. Timofey wandered southward, to join briefly the ranks of Denikin's army, while Mira's family escaped from the Bolsheviks to Sweden and then settled down in Germany, where eventually she married a fur dealer of Russian extraction. Sometime in the early thirties, Pnin, by then married too, accompanied his wife to Berlin, where she

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher