![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

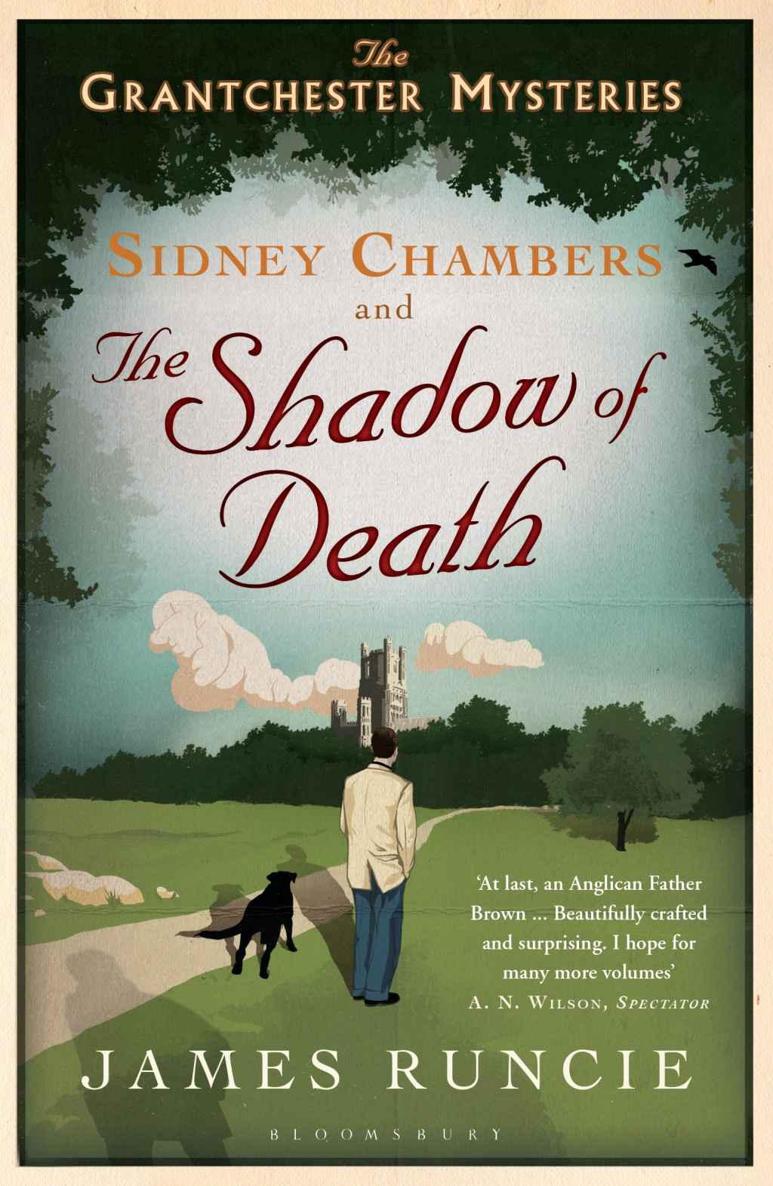

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

‘too common by half’ and Matthew had joined a skiffle band that included ‘all kinds of riff raff’. Perhaps their elder brother could go and knock some sense into them, she wondered? Sidney thought that this was not really his business but the plain fact was that even before he had involved himself in this criminal investigation he had had too many things on his plate. His standards were slipping and the daily renewal of his faith had been put on the back burner. He thought of the General Confession: ‘We have left undone those things which we ought to have done; and we have done those things which we ought not to have done . . .’

He started to make a list, and at the top of the list, as he had been advised at theological college, was the thing that he least wanted to do. ‘Always start with what you dread the most,’ he had been told. ‘Then the rest will seem less daunting.’ ‘Easier said than done,’ thought Sidney as he looked at the first item on the list of his duties.

‘Tell Inspector Keating everything.’

It was a Wednesday morning, and he knew that a visit to the St Andrews Street Police Station would not be popular, but Sidney was so convinced by the accuracy of his deductions that he decided the truth was more important than Geordie Keating’s impatience.

‘I hope this is not going to become a habit,’ his friend warned, as he pushed an old cup of tea on to a stack of stained papers and began a new one.

‘Not at all, Inspector. I do have more information that I think is important.’

‘My life is a river of “more information”, Sidney. Sometimes I wish someone would put a dam in it. I presume that you are referring to the solicitor’s suicide.’

‘I am.’

‘Then you had better sit down.’

Sidney wondered whether he should have rehearsed what he was going to say, written it down even, but there had been no time for such preparation. Consequently, his thoughts came out in a rush. ‘I have been thinking about the circumstances of the crime, the people involved and the nature of love.’

‘Oh God, man . . .’

‘And I just cannot believe that Stephen Staunton meant to kill himself. I know that everything suggests that he did so but I do not believe this to be the case. Nor do I believe that he drank any of the whisky that was on his desk . . .’

‘Then what was it doing there?’

‘A red herring, Inspector. It was even, perhaps, a way of pointing the finger at Clive Morton, a man who does not know as much about whisky as he possibly should . . .’

‘That does not make him a murderer . . .’

‘I do not think that he is . . .’

‘Well, that’s a relief . . . it only leaves every other inhabitant of Cambridge as a suspect. I don’t suppose the victim could still be responsible for his own death? That the case could in fact be suicide?’

‘You remember at the very beginning of our conversation on this subject when I suggested that things could be too clear?’

‘I certainly do. It was a bit cheeky of you if you don’t mind my saying so.’

‘I don’t. But this was the murderer’s mistake. Knowing that I was on the case she began to panic. In fact she panicked so much that she was forced into producing her trump card: a suicide note.’

‘She?’

‘Yes . . . “She” . . .’

‘You’re suggesting our man got his secretary to write his own suicide note? You’re crackers.’

‘I am not, Inspector.’

‘Then what are you suggesting?’

‘I am proposing that the letter is not a suicide note . . .’

‘Oh, Sidney . . .’

‘Look again, Geordie.’

As Inspector Keating examined the piece of paper Sidney recited the text he had memorised.

A,

I can’t tell you how sorry I am that it has come to this. I know you will find it upsetting and I wish there was something I could do to make things right. I can’t go on any more. I’m sorry – so sorry. You know how hard it has been and how impossible it is to continue.

Forgive me

S

‘Seems pretty clear to me,’ Inspector Keating replied.

‘Too clear; and then again, not clear enough. For this is not a note written by a man who is about to kill himself. It is the note of a man ending a relationship.’

‘Yes, I can see that it could be . . .’

‘And you remember the private diary, the one with the entries in pencil that Mr Staunton rubbed out each day?’

‘The one with the days marking the mornings and the afternoons? The one that might suggest a few

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher